A conversation in the exhibition ‘Medieval Bodies’

Tobi Maier: Good afternoon, I am Tobi Maier, director of Galerias Municipais. I would like to welcome you all and thank the whole team at Galerias Municipais for organising today’s talk and of course for installing the exhibition Corpos Medievais by Pedro Neves Marques, curated by Luís Silva, which is where we are now. I’ll give a brief introduction and then we’ll get into the conversation with Pedro and Luís. We’ll also have the possibility to dialogue afterwards about the works on view, as well as ideas and questions that might come during the talk.

Pedro Neves Marques is a visual artist, filmmaker, and writer. He has had solo exhibitions at CA2M [Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo] (Madrid), at CaixaForum (Barcelona) (which is still on view), and in many other institutions around the world, such as Castello di Rivoli (Turin); High Line Art and e-flux (New York), Gasworks (London), the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, at the Museu Coleção Berardo here in Lisbon, many other group exhibitions, as well as film festivals, including the Toronto International Film Festival, New York Film Festival, among others. Pedro’s full bio is also reproduced in the gallery handout.

Luís Silva is curator and co-founder of the Kunsthalle Lissabon, and returned a few days ago from São Paulo, where, together with João Mourão, he opened Manuel Solano’s exhibition at Pivô.

I would like to thank you both for accepting the invitation to work with us on the exhibition here, exhibiting works that have never been shown before in Lisbon, and in Portugal, and developing a new piece for Corpos Medievais [Medieval Bodies].

Finally, I´d like to mention the collaboration with HAUT who is a sound artist, music producer and performer working across experimental electronic music, dance and human-computer interaction. HAUT was working with us here during the days of the installation and his contribution was indispensable.

Thanks to everyone of you for being here today.

Luís Silva: Should I begin, or would you prefer to start?

Pedro Neves Marques: I think you start.

LS: It’s a bit difficult to be the curator starting, it puts me in a complicated hierarchical position… [laughs]. Good afternoon, thank you for coming. This is a project I have a very special affection for. My professional relationship with Pedro goes back some years now, but until this moment we never had the possibility to collaborate on a solo exhibition, especially an exhibition with the scale and ambition of Medieval Bodies. What you can see here is a set of works that, despite having been shown in different contexts and situations, all belong to the same conceptual, discursive, and narrative body of works. They are presented here together for the first time, which adds to them new contours, opening up new possibilities, and it was very, very gratifying to be able to see them all together. We also worked on the presentation of a new piece [The Early Death of Sigmund Freud, 2021]. As Pedro knows – because we’ve talked about it extensively – this is a piece that I like very much, because it ends up decentring and repositioning the debates suggested by these works in light of a completely new and distinct context. I think it was a very productive addition to this body of works.

Pedro, I’m talking about your works here, as if you weren’t here, which is always quite awkward. What was this process like for you? The author´s narrative is always quite distinct from the curatorial narrative, and although these projects have never been shown together, they exist because of your subjectivity and they exist as a coherent body of work within you. They materialise here for the first time, so your position is quite different to mine. How does it feel to see them all together for the first time?

PNM: Yes, inevitably, the pieces find each other, don’t they? Perhaps to open up the pieces somewhat, I can say that they all seem very coherent now but it’s curious that, in fact, many of them initially came from very mundane situations. Funnily enough this often happens to me, that is, relatively mundane situations that then trigger processes that last for years. For example, the key piece, Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, from 2019, departs from this slightly unusual idea of a cisgender man being able to gestate ova through an ovarian implant – and I feel like I’ve already lost half my audience by saying this… [laughs] It seems like a completely nonsensical idea, and yet it carries very specific thoughts. The narrative arises out of a real online literary and aesthetic subgenre called Mpreg (male pregnancy) – you can go on Amazon and buy ebooks about it or download these stories online – that have diverse themes: Mpreg in space, Mpreg with werewolves, normative Mpreg, whatever a person wants. I have a great appreciation for these kinds of sub-genres, which are a bit fringy and regarded as “minor”. I met someone at a dinner party who made a living out of writing these kinds of books – and of course I approached that person straight away, I’d like to know more. It made perfect sense with several of my previous works, for example, and that triggered a process: I started reading several of those books and suddenly found myself writing, or rather, thinking about my critique of what I find interesting in that gay literary sub-genre: two characters, usually a more masculine one understood as, well, the “daddy” of the relationship, and an effeminate character who gestates… In those books the pregnancy images are much more literal than I make them seem here in the show, because there are bellies and all that stuff, which don’t interest me much. In the end, my critique took the form of an Mpreg story as well, which is what you can hear in the central piece, initially presented in the context of the Illy Present Future Art Prize at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin.[1] It’s been some time now, the pandemic has happened, hasn’t it?

LS: Pre-pandemic…

PNM: Pre-pandemic… it seems like it happened millennia ago… On that occasion, the piece was presented in a very small but very interesting room. It had an arch, just like this room, but it also had a window facing the street. I built the piece more or less like we replicated here visually, where you have the television, in which I’m reading my poems (although you can’t hear them) with my back to the window, and the sound piece around it. In that installation, when watching the film you had the street as a background. For the exhibition here at Galerias Municipais – Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional, because this is an open space, I found it interesting to build a window inside the exhibition itself and thus create a certain spatiality, some sort of depth instead of just having a white wall for a background. But back to your question: I finished this first piece, but there was so much to it that I just kept working. I find this interesting: to voluntarily persist and stay with your ideas rather than jumping right into the next one. So I ended up writing a series of poems – some already included in the installation – that resulted in this series of photographs titled Autofiction Poems [2020]. Later came these other two films, The Ovary and Meat is Not Murder, both from 2021, which, not being exactly a diptych, were first presented together at the Liverpool Biennial 2021 and now here as well. They work like two micro-stories, so to say, one of them obviously very much related to the central piece, Becoming Male in the Middle Ages. At this point I thought [all this work] was finished. But then, I kept thinking, I mean, somehow, I started to…. I’ve always had a very complex relationship with psychoanalysis, but this sequence of works, related to sexuality and, obviously, to gender, to the construction and expectations vis-à-vis these categories – psychoanalysis is a constant in these works, isn’t it? So I ended up writing a story that turned into the animation video The Early Death of Sigmund Freud [2021]. At first, I wasn’t sure about including it in the show, but you, Luís, I remember you saying, “But psychoanalysis is already in all these works… – make the work!” [laughs] And of course, here we have it.

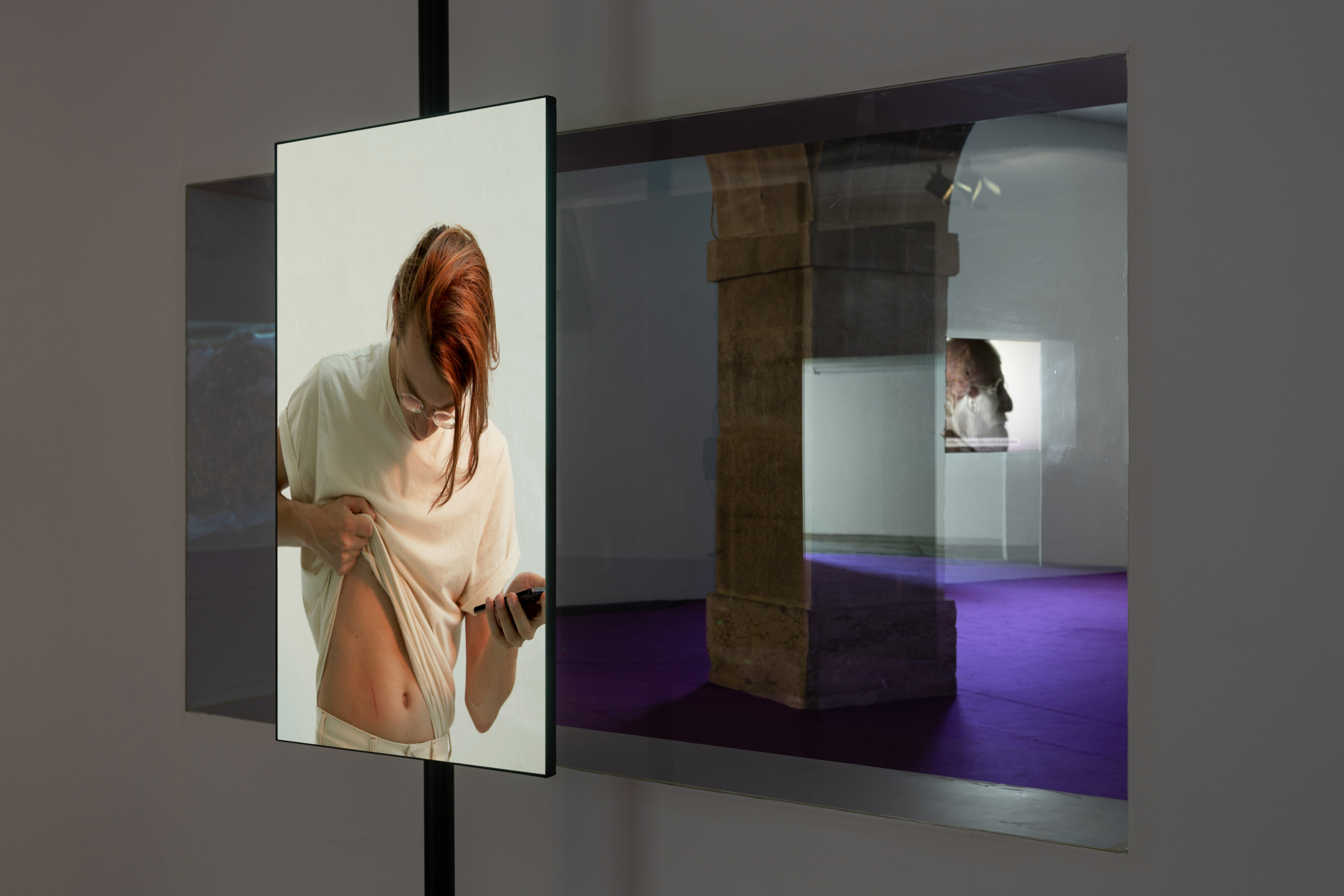

Pedro Neves Marques; Becoming Male in the Middle Ages (2019) and The Early Death of Sigmund Freud (2021); Exhibition Corpos Medievais; Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional; 2021. © Bruno Lopes

LS: There are a thousand and one threads we could follow here, but going back a little bit here to Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, to the show’s central piece – because you referred to it as the axis that structures the exhibition (even because, chronologically, it is the first to appear) – can you tell us more about its narrative? Because you said that you wrote this story that can be affiliated to Mpreg, but at the same time it also ends up being… you said critical… I don’t know if it is critical, but it is at least less normative…

PNM: It dialogues with blind spots…

LS: Exactly, exactly…

PNM: It’s interesting: every time you make a new piece you reflect on what you made before. The issue of reproduction, for example, is a theme that for some people will be more evident, for others completely invisible, but that features in many of my works. Here it is clearly at the core of the exhibition: what reproduction does to sexuality (sexuality on several levels). This issue is clearly found in the literary works I mentioned, the subgenre of male pregnancy, which is grounded in many gender expectations found within a male gay imaginary. In it there is no room for other gender identities or for any other kind of gender fluidity or orientation. As a literary genre it interested me because, for all its spectacularity and bizarreness, it is curiously quite normative. In the end, my approach was not quite a critique, because it wouldn’t make sense to critique that sub-genre for what it is – even though I published an article about it in the Liverpool Biennial catalogue. Still, going back to your question, these works pick up on those blind spots of normativity and desire, that tension between rupture and an LGBTQI+ legacy and the normativity also present in those categories today: the nuclear family, marriage, desire for biological reproduction, surrogacy… Mine is, in fact, a story between two couples: a straight couple and a gay couple in their thirties – and I think we can talk a bit more about that idea of “middle age”. In the case of the straight couple, you have a female character who categorically never wanted a child, but her partner, who was always empathetic about her not wanting a child, suddenly says he wants children. It’s a defining moment, shall we say, in their relationship. She ultimately gives in, but then I end up creating a plot twist in which the viewer realises that they can’t get pregnant for infertility reasons – and I then explore these various nuances, because the expectation is always that infertility is female, never the man’s. In fact, statistically there is far more male infertility than female. It’s a telling blind spot. At the same time, you have the other couple: two gay men. One of them decides to implant an ovary in his body in order to gestate, for three months, eggs in his body, which are then extracted from him and inseminated through a regular insemination process, IVF. This is where the science-fiction speculation comes in, although it is very subtle. I should also say that these couples are good friends, because I was very interested in that aspect of friendship as well. I thought a lot about Friends, I confess, I thought a lot about the Friends TV series… [laughs]

LS: A 21st century version of Friends…

PNM: Becoming Male in the Middle Ages is a highly narrative piece, of course, that tells this story about the dilemmas faced by these characters, mainly from the point of view of the female character, how she reacts to it all. Here the installation is at the centre of an open exhibition space, so I think the tendency will be to listen for five minutes, go and see another piece, and, if you have the energy, come back to see another five minutes. We printed the chapters of the story on the wall to help and guide visitors. The first time it was shown, this was not the case: it was exhibited in a very intimate room and visitors actually stayed for the entire half hour of the piece. This narration is then interspersed, almost as if it were a podcast, with more technical and journalistic moments about all these insemination themes. Ovarian transplants are not really an idea I came up with, only the implantation of ovaries in a cisgender man. But who knows, maybe in twenty years’ time this won’t be that strange, because hormonally it is not unlikely to insert a functioning ovary in a body originally without this organ. Finally, I also asked friends close to me to make statements about the story itself, which resulted in very beautiful and intimate moments.

LS: You were talking about the narrative, and you were talking about the two couples, a straight couple and a homosexual couple, that relate to this idea of reproduction. But this narrative somehow draws on your image, and the image we see is of you scrolling through a phone. And making the connection, perhaps later with the poems, how do you conceptualise your image? Also, by stating your image, are you automatically stating your persona? Yes or no (in the light of these works)? Or, basically, what is your relationship, in these works and in general, for example, with these strategies that you know so well, of autofiction on the one hand and autobiography on the other?

PNM: The tension that I find interesting in autofiction is between what is mine and what is not mine, and the way in which those voices blur together. How do I write something that comes from my personal experience, but is contaminated by someone close to me who is in a process of pregnancy or in vitro insemination, or a gay couple in my circle of friends who confesses their reproductive desire to me? For example, how when coming out as gay at sixteen all one of them could think about was that he wouldn’t have a child – this is incredibly powerful, a sixteen-year-old to be thinking about reproduction…

LS: About biology.

PNM: About biology because of a sexual orientation. There is a confusion between what is mine and what is around me, and that is very clear in the poems. In relation to that piece, maybe because of that aspect of intimacy, I suddenly, yes, I found myself in the work visually, reading my poems. Poetry became very important for me precisely because, how shall I put it…. Anyone who is familiar with my work knows how it often has very explicit political undertones…

LS: Or discursive.

PNM: Or discursive. Although, of course, the works always have their own particular weirdness, right? You’ve got androids, and you’ve got transgenics, and you’ve got the mosquitoes and all the rest of it. I wrote a poem that says, “If I write about me it’s because everything else I write about is not about me.” That’s it. How could I not be in the work? But then there’s that aggressive gesture of: no, you’re not going to listen to me; you’re not going to hear my poems; you’re going to glimpse them, you’re going to read them but won’t hear my voice. At that moment, when I was doing the main piece, that was the spirit I was in: no, I don’t want you to hear my voice reading the poems; I want you to hear my voice telling the story of these other characters that are not me. Later, I placed the cards on the table in this series of poems, where clearly there is a very strong autobiographical voice.

LS: And the series is called…

PNM: It’s called Autofiction Poems, and yes, it’s a whole series in which there’s this confusion of voices, of what’s mine and what’s not mine, but in which experiences are always channelled through me. I’m the filter.

LS: How is that confusion of voices productive or not, as a mechanism of identity construction? Do you get what I’m asking?

PNM: No. [laughs]

LS: There’s a tendency to think of, for example, personality as a stable, unchanging entity throughout our lives, [something like:] that’s our identity, it’s always been that way and it’s always going to be that way for the rest of our days; there are fluctuations, but they’re fluctuations that in no way call into question who we are. What I was asking is whether by resorting to an auto fictional strategy you are not calling into question this whole identity construction of immutability? I’m asking, if that’s so what interests you in that? Because there’s a whole range of studies on the uniqueness of personality, of identity, and what I find very interesting in this autofictional strategy is exactly how you call that into question. You’re saying: this thing we call our identity is fluid. It is subject to pulls, to pushes, to performativity, and it’s good that it is so, because we must dismantle it somehow. This is what I feel here, or at least how I look at these autofictional strategies of yours.

PNM: You’re asking about several things: first, what does autofiction, this fancy word for autobiography… [laughs]

LS: Or dialogic…

PNM: …more dialogic.

LS: …which comes to question the very notion of autobiography.

PNM: Yes.

LS: And that’s why I find it so interesting.

PNM: There’s a violent gesture in autofiction and in how you decide to narrate your biography – that aspect of violence is also in other works of mine, in their own ways, isn’t it? There’s a moment in the central piece where this is explicitly stated: that violence is found not when a writer tells the truth, but, on the contrary, when they feel the need to fictionalise. Violence is that need for fiction. It might feel counterintuitive, right? If you explicitly talk about a person who is your friend in a story or in a book, it may feel like a violent gesture, but the need for fiction also has this side of violence towards the people around you and who later end up being your work material. There is this aspect of violence in several of the poems, and the fact that you, being the author, act as a filter for all those experiences. You find this in many of my works, and even theoretically: a relationship with alterity, with difference, and how difference inevitably constitutes you, that whole game. And it is a difficult game, it is a violent game, it is a violent constitution. This happens here as well, but at the scale of a more intimate circle. I’m very careful with the word community, for example – perhaps because I lead a rather erratic life – but everyone has a circle of people, right? And here suddenly that circle of people became the work, some people more explicitly than others.

LS: It’s that kinship, which is very difficult for us to translate…

PNM: The affinities…

LS: Yes. But changing subjects, you were talking about your texts and about when you write in a more theoretical or more cryptic register, and I wanted to use that to contextualise your interest in these “minor” genres, as you referred to them. We’ve already talked about science fiction, but you’re also very interested in horror and the erotic. And these works are, in a way, quite explicitly science fiction, but when you look more closely at them it’s a science fiction of a future so close to us that it could almost be mistaken for the present, and from that moment on it stops being science fiction, it’s just an alternative present. The codes of science fiction are very important to you and for this exhibition. For example, the two films that come from the Liverpool Biennial, which are shown here, end up functioning almost like two science fiction tales. On the one hand, a narrative about implanting an ovary in the cis male body. And then, with irony, humour, and almost a certain perversity, the story of a vegan who, when eating meat that has no relation whatsoever to an animal, feels the same adverse reaction as if it were meat coming from an animal. What does science fiction allow you to do?

PNM: So much.

LS: Things that, for example, a more documentary genre wouldn’t allow?

PNM: Well, for one thing it’s interesting that you’ve introduced the word documentary now…

LS: I felt I needed to narrow down the field of possibilities for you.

PNM: Exactly. I find this encounter extremely curious, and you can see that in several works of mine: there is a very concrete register to them, very tangible, almost documentary-like, even in the way I film sometimes, depending on the work, but then it doesn’t make any sense, insofar as there’s a completely unusual speculation. I think that, very often, science fiction… Well, for one thing, there is an appreciation and a fondness for the genre, let’s be honest. But more specifically, it’s an interesting tool to, again, observe blind spots. Because it’s not simply about the exercise of fiction, it’s the exercise of speculation. You simply nudge what’s already there in front of you, and in that sense it’s a more sociological exercise, more than science fiction in the clichéd sense.

LS: Yes, yes..

PNM: Anyone who likes science fiction knows that the genre has already been quite deconstructed and nowadays functions almost as a sociological exercise. On the other hand, science-fiction is about using certain standard images and characters (the android or the pregnant man), because they already carry a set of expectations. They offer a starting point, in terms of work, which is great, because you already know partially that your audience is going to see the work and say “Ah, it’s the pregnant man”, for example – and this immediately channels a series of expectations.

LS: Yes, yes, when you say “an android”…

PNM: Exactly.

LS: You’re already activating…

PNM: …you have a series of mental images…

LS: Yes, yes.

PNM: …and made-up ideas.

LS: Yes, not least because it’s curious that – let me just interrupt you – you use the female pronoun for “an android” (in Portuguese)…

PNM: That’s a whole story. [laughs] And there’s the book coming out that I can say is about that.

LS: Okay. [laughs]

PNM: I edited an anthology with Centro Dos de Mayo in Madrid, that’s coming out this month, finally, after a long process, which is about the image of the android and how gender and colonialism are core issues in the history of such characters. But this is a parenthesis for those who know my other works. What I mean is that you can work right away with certain images, with this immediately grabbing the viewer’s attention, and from there you’re able to construct your stories in another ways and see what happens in those tensions. For me it is a very productive working process. I was going to say something else about science fiction, which is: things are already much more science fiction than we often think, aren’t they? And it only takes a small gesture to unlock those underlying tensions. I don’t know if I’ve fully answered your question.

LS: Yes, I think you have.

Pedro Neves Marques; Meat is Not Murder (2021) and Autofiction Poems (2020); Exhibition Corpos Medievais; Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional; 2021. © Bruno Lopes

PNM: Another thing I wanted to say, because we haven’t talked about it is that, while the film in the background over there, The Ovary [2021], is clearly about this narrative we’ve been talking about, the other film, Meat Is Not Murder [2021], also comes from a personal situation. Me and a friend of mine from New York, who teaches at the Graduate Center on Art and Animal Studies and is a staunch vegan, at one point we had a conversation about lab-grown meat. There are labs and start-ups in Israel and the Netherlands, for example, developing a technology that seeks to produce animal meat from mammalian cells. They don’t even have to be from a specific mammal. In critical terms, you can start with the meat itself, but you quickly end up questioning how this will change the meat industry and an entire economy. I had that conversation with this friend of mine, “Look, would you eat this or not?” It was from that conversation that I wrote the piece. And why is this film here when it might seem somewhat unusual? For me, it’s about the rootedness of the body as malleable and the artificiality of all these categories. It seemed like a curious image to mix with questions about gender.

LS: Yes, yes… and reproduction.

PNM: But also reproduction, yes. A laboratorial reproduction.

LS: Bodies, cells reproducing, multiplying.

PNM: Yes, that’s it. That ovary is just like that lab meat, apart from an underlying history of violence related to gender.

LS: I don’t know, maybe we’d open to the audience.

Audience 1: If that robot attack against Freud had actually happened, how do you think sexuality or those gender issues would look like in today’s world?

PNM: Well, for one thing, it’s a redundant exercise, isn’t it? That film is kind of a redundant exercise.

LS: Rhetorical…

PNM: If it wasn’t for Freud, someone alongside Freud, as Freud’s biography shows, would have invented the minimum standards of what later became psychoanalysis, wouldn’t they? I found myself reading biographies of Freud – something I never thought I’d do – and it was a, let’s say, tedious but interesting exercise. Psychoanalysis is everywhere, it is impossible to escape from psychoanalysis, even if Freudianism today is a bit of a niche thing, even in the practice of psychoanalysis itself. Sure, we can go to a highly Freudian psychoanalyst, but that’s no longer where psychoanalysis is going. Freud has been highly deconstructed, as we all know. But yes, simply this exercise in anticipating Freud’s death through robots, or nano-bots, sent into the past, is science fiction. It is a what if story? What would the twentieth-century be without the presence of these theories and prejudices? As emancipatory as, on certain levels, Freudian theories were, they were also highly problematic. What I do is simply this exercise in imagining a life without Freud. In fact, as much as “killing Freud”, I was interested in “sending robots to the past.” [laughs]

LS: Yes, but you could have sent the robots back to any time in the past…

PNM: Yes, but, sending them into Freud’s brain… It’s a vicious circle, that piece. But hopefully it works.

LS: I agree pretty much with what you said, in the sense that if it hadn’t been Freud, it most likely would have been someone else, which always makes me think of that dialectic between invention/discovery. And if you assume that it was an invention, then I don’t think there’s any requirement that it should be an invention. If it’s a discovery, then yes, I think the inevitability is more present. Anyway, if it hadn’t been Freud, it most likely would have been another straight white European male, so all the violence associated with the construction of psychoanalysis and how it operated from that point on – on our identities, our bodies, our desire – was going to be pretty much the same. Also disagreeing relatively with you, yes, Freudianism was deconstructed and it was criticised and it was relativised, but certain of its aspects went “mainstream”…

PNM: Yes, exactly, psychoanalysis is everywhere.

LS: …and which are still quite present today and which are quite violent. For example, the concept of hysteria, as something that affects women, that women are hysterical, comes from here; also that question of homosexuality as an inversion of desire, that’s another one. And all of this entailed a brutal history of violence on our bodies, which even though it has been deconstructed clinically…

PNM: Yes, it’s part of the social substrate.

LS: …it’s part of our everyday lives. My enthusiasm for this piece comes from that: because there is a set of narratives that are still quite present and that I think are very interesting when put in contact and in dialogue, or in antithesis or antagonism, with the narratives of the other pieces.

PNM: Yes, maybe what would the twentieth-century have been like under, for example, the influence of Carl Jung?

LS: Imagine if we were doing that exercise now, and it wasn’t Freud who was there…

PNM: The deconstruction of Carl Jung, of Jung’s archetypes.

LS: There you go, but it’s the exercise in science fiction that makes it interesting.

PNM: I would even venture to say that I think it’s the child at the end of these films and of the installation Becoming Male in the Middle Ages that sends those robots back in time.

LS: Did we have that conversation, or not?

PNM: I’m not going to say whether I’ve written that story or not.

LS: Ah! [laughs]

PNM: But maybe I did write it… [laughs]

LS: No, my theory is that it was the character in whom the ovary is implanted that then sent…

PNM: No, it’s the child that comes out of that process.

LS: It’s the child, the child… [laughs]

Audience 2: Pedro, you have been talking about science fiction as a thread, not only of this exhibition, but of your work in general. I would like you, beyond the issue of science fiction, to talk a little more about the issue raised by that video about Freud, which is basically an issue of virtuality, right? All those biographical moments that you find are situated in the event of possibility, the eventuality, of not being, of being a kind of impotence, and from there a possibility arises, virtual. And in fact, the whole exhibition is traversed by multiple virtualities.

PNM: Yes, I see.

Speaker 2: This is not a question, it’s just a suggestion: if you could speak a little more on the virtues of virtuality. [laughter]

PNM: Yes, in fact, when you put that way, there’s that leap, that virtuality in my work. I think you’re asking virtuality in the sense that Gilles Deleuze uses the word, not virtual in the sense of the digital, but of what is coming, in potency. I don’t have a clear answer, but again, I go back to the question of expectations. When you get into that process of virtuality or projection, of trying to keep up with that possibility, there is a cycle, there is a feedback loop. You start building with what already exists. And from there, you manage to work small ruptures, you manage to conceptualise small political ruptures. And of course, this happens purely in a controlled environment, often fictional or fiction-based, because they are fictional ruptures. On the other hand, science fiction is not about the future necessarily – that’s a very reductionist view of what science fiction is. It’s about the scientific, about science, and it’s about technology. For me, it’s very much about those kinds of elements – the aspect of futurity is just inevitable. But there’s also a politics about the future and how we appropriate the future, that is, how we advocate for the futures we want.

LS: How do you imagine future…

PNM: …instead of the future that is imposed on us. I’m already getting into theory, but the exercise of producing the future (and here I say future in the singular) is political; it’s always happening and it goes from Elon Musk to the troika, to whatever. The production of the future is a constant political exercise that often surpasses us. So, yes, this virtuality also has a lot of roots in how you defend the possibility of futures that are not the only future. And, of course, in the works exhibited here, this question arises in small gestures, in small narratives. But yes, I can say that, in conceptual terms, there is this substrate of engagement, of imagining another way. And this is what happens in each of these pieces, in each film, in each story, it is tailored to the context that I am addressing, be it GMO, be it a family relationship, be it gestation and reproduction. This is a process that I have come to understand for myself, in my work process. If you came to ask me about these topics 5 years ago, maybe it wouldn’t be so clear, but now I easily understand the future as a space, a field, also in itself political. On the other hand, and here I venture a bit, you often have certain fields of society that battle for other futures in a more explicit way than others. The queer and LGBTQI+ movements have clearly built futures and continue to build futures; racial issues build futures; and, I won’t forget, issues of class build futures.

LS: But there…

PNM: By the way, sorry to interrupt you, because the aforementioned issue of class leads me to something that hasn’t been talked about here and that, for me, is actually essential to this whole process. If in other works of mine there is a very close dialogue with Indigenous issues (in Brazil and in my experience in Brazil) or even a certain queer context that I found in Brazil, here we have an exhibition about whiteness, don’t we? It’s an exhibition about privilege and even whiteness – that seems to me to be explicit. Clearly, the debate that’s happening between those characters is a privileged debate.

LS: Of those who have a house to live in, who have…

PNM: Exactly. The female character says, “I’m going to visit them in Clinton Hill.” For anyone who knows New York, it immediately demarcates the class of these people. The very question of lab meat or even paying the costs of psychoanalysis.

LS: Yes, yes…

PNM: It was important for me, too, to do that exercise. Of course, I know that I am a white, European person who has worked, for example, a lot in Brazil. And it is also important for me to “come back home” and observe other systems.

LS: Yes. Taking a step back, because you were talking about LGBTQI+ movements, racial movements or even class struggles as producing or trying to produce futures, and basically political struggle is a struggle about the future.

PNM: In a generic way, yes.

LS: There’s a question there…

Audience 3: Hello.

PMN: Hi, how are you?

Speaker 3: I wanted to ask a question about poetry…

PNM: Oh, great, finally. [laughs]

Audience 3: …because you said something that I kept thinking about. It was something like: I do with poetry… or, everything that I am is mediated through poetry. And bearing in mind that all the pieces are influenced by challenging the structure of science fiction (and in which the issue of temporality is always played with, either [in the form of a uchronia], as you do with Freud, or in the other pieces, then, from a creative point of view – and not only from the poetry medium, but also due to the fact that there is a tension between a photographed poem and a published poem), how do you think about this? I’d also like to hear more from you about this idea that poetry then is “raising a diagonal where I’m not”.

PNM: Maybe I expressed myself wrongly. I started writing poetry recently, but poetry, for me, has gained a lot of space. In New York, when I lived there, I frequented its poetry scene quite a lot – to be honest, during those years the New York literary context was one of the things that offered me the most – and I learned a lot from those people, by listening to them, reading them, reading with them, etc. Now, how does poetry come into the visual work? I suddenly realised that poetry was wanting to enter my work – I say it like this because you don’t control these processes, they just happen – in an exhibition context. I am not particularly interested in visual exercises, as with, for example, the work of Salette Tavares, Ana Hatherly or E. M. de Melo e Castro – despite the immense affection I have for their work. I am rather interested in poetry as an element of fragility and intimacy that establishes not necessarily a feeling but an atmosphere.

LS: An affection.

PNM: An affection, yes, an affection; a feeling in an exhibition. You go to an exhibition… For example here, you walk in, maybe the first piece you see is Autofiction Poems [2020] and you read a series of poems. For me, having poetry on display channels you and puts you in a mood, presents you with a voice and sets up an atmosphere. And that, for me, is already immense! That, for me, is already a lot for an artwork to do. It has already produced something. In other words, with this I also mean that poetry is not only a support for the rest, because it is essential. And that’s a bit how I’ve come to understand the way I’ve been exhibiting poetry. In this case, as you were saying, the format is photography, not the actual poetry. I ask myself why, whenever I am composing and trying to translate poetry into a visual object to be presented in a gallery, when the poetry begins to take on very graphic outlines, I lose interest. I’ve realised that that’s not what interests me. My poetry is humble, it’s small, it brings you closer, you must read it, it’s not big. And here, I found it funny – and I confess it was after the event, because, well, you don’t always know what you’re doing – that as a spectator you’re looking over my shoulder at my mobile phone, meaning that you have a voyeuristic element to the photos, so to speak, which has a lot to do with peeping into someone’s intimacy. I do a lot of writing on my mobile phone, and it was only when I saw the photographs that I realised where I had put the camera. I write a lot on my mobile phone and I like that, because you can’t compose the poem straight away, because the line breaks, the metrics, they don’t work, or if you want to invent a verse, that’s a bit tricky to do there in Notes, but you also discover some unexpected forms by using it. You have to do your homework afterwards. The other day a person I know from New York came to see the exhibition, and at the end we left, and he looked at the banner and said, “Kind of brave to put an image of a mobile phone as the exhibition’s banner image…”; and I said, “Yes, indeed…” It’s the most intimate object we have, everything is there, there are our private photographs, there are…

LS: Your relationships…

PNM: … our relationships.

Audience 3: Thank you.

Audience 4: Pedro?

PNM: Yes?

Audience 4: A curiosity: you have a lilac floor to this exhibition. I would like to hear you talk a little bit about this colour and how it plays a part in the exhibition.

PNM: It’s the process of installing, isn’t it? Clearly, we needed a carpet because of the sound and when I did the show’s central piece, originally, it was a soft cream/salmon colour that I used, but it got very dirty… [laughs] Purple is an aesthetic choice and I won’t go into its potential symbolism, but yes, it’s a strong presence. I don’t have a particular fondness, I confess, for creating environments, that is, for me that’s not a particularly important element in the construction of an installation – which can be annoying, for example, when you exhibit in large spaces like this one. But the theatrical aspect of a show, that’s what I mean, is not essential to me. But you have graphic elements that then, of course, constitute the piece, yes.

Audience 5: I just wanted to hear you talk a little bit about the collaboration with HAUT, the composer, because I think sound is a very strong element to the show. I wanted you to tell me more about that collaboration for this exhibition.

PNM: I’d worked with HAUT before in an installation and a film. Here I knew I wanted to fundamentally make a sound piece, which, for me, is a challenge. Sound is an important element of my films, but I don’t really do sound pieces. So I invited HAUT, who ended up doing the sound for the installation and for the two films shown here. It is also worth mentioning that a short film is about to be released, which is the culmination of all of this, and HAUT also did the soundtrack for that forthcoming film. So there is a great intimacy between us. We know what we’re both thinking, which makes the process very easy. And HAUT… is amazing. They have a great sensibility. Maybe it’s because of having a degree in medicine; HAUT initially comes from a medical background.

LS: Really?

PNM: Yes, HAUT did medicine. And I think that gives them, and we’ve talked about this, a very tactile sensitivity. There’s really great affection in the way they listen to music. And that for me is incredible, because that’s often what I want from music. By the way I’ll take this opportunity to talk about the process of working between us: I knew I was going to have this piece [Becoming Male in the Middle Ages], it was going to be a short story with some podcast moments – how do you put up with half an hour of this? From there we talked a lot about club music, which is the context that HAUT comes from, even though they don’t produce club music, but it drives their output. I wasn’t really interested in club music; I was interested in the feeling of being in a club listening to good techno, that is, not the music but the feeling. And we also talked about pop, we talked a lot about pop. Again, I’m not interested in pop music, but I am interested in a fuzzy feeling, a warmth that pop offers, a comfort. So we talked a lot about these two extremes, and that’s a bit of what, if you listen to the piece today, you might have that feeling. You might understand what I’m trying to say. And then, because we got to talk about Lana Del Rey…

LS: Ah! [laughs]

PNM: When we were doing this piece, when I talked about pop with HAUT, I told him about Lana Del Rey – whom I love, there you go, it’s out in the open… [laughs]

Audience: [laughs]

PNM: Seriously, I like Lana Del Rey, and let’s not theorise why we like certain musicians.

LS: Or are we going to…?!

PNM: But there are indeed fascinating things about Lana Del Rey’s work. Her previous album, Norman Fucking Rockwell! had just come out. It’s an extraordinary album. And I talked a lot about that album with HAUT and what that pop feeling was that I was thinking about. And then, when the Liverpool Biennial commission came and I started to work on the two films here on show, HAUT literally sent me a cover of Lana Del Rey’s Let Me Love You Like a Woman, which was a relatively recent song of hers, a cover that I hadn’t asked for… In other words, HAUT took our conversation literally.

LS: [laughs]

PNM: And it’s incredible this song, and I’m even sorry you can’t hear it perfectly, because of the architecture of the space, it’s difficult. Actually, that film, The Ovary [2021], was put together by way of that music, because I didn’t know what to make of the images. But I had HAUT’s music, and Lana Del Rey’s music, and suddenly I had that image of the central character at the gynaecologist and it was from that image that I built the film. I remember being – actually it wasn’t my studio, it was someone else’s studio – working, and it was beautiful to see that music play on top of that image. So I ended up constructing this little film, which is almost a music video, from that image and that music.

Pedro Neves Marques; The Early Death of Sigmund Freud (2021) and The Ovary (2021); Exhibition Corpos Medievais; Torreão Nascente da Cordoaria Nacional; 2021. © Bruno Lopes

Audience 6: Hi. I just wanted to know a little bit more around Medieval Bodies and those connections with other studies that are important in the history of feminism and queer studies today… I can imagine connections with that…

PNM: Yes, thank you. Becoming Male in the Middle Ages[2] is the title of a book, which I read a few years ago; a study about the construction of masculinity in the Middle Ages. That theme is not necessarily important for my work, but the title stuck with me. And then Medieval Bodies[3], which I actually remembered yesterday when I was looking at my library, is also a book. On the one hand they are just titles and there is a poetics to it that interests me; on the other hand, there is an idea of medieval times, not necessarily historical medieval times, but of a period, coming from what existed before and knowing what came after, of great confusion, where a number of paradigms are worked on and truly revolutionised. I am thinking in particular of the body, gender, the category of woman, of man, and a series of relations that are constituted through divinity. As you mentioned, it’s interesting that in recent years there has been this great movement of queer medieval studies, which for obvious reasons seeks to find references in the past. Mainly, perhaps, I would say, coming from a more trans, non-binary context. I think you have a lot of work being done there, and it has its problems, but that’s another conversation. Lastly, and in a completely different sense, you have the middle ages, or that idea of the middle, in the lives of the characters. They are characters in their thirties, and my pieces also talk a little about this, a phase of life which I’m also going through and where these issues we have talked about today come to the fore for many of us. Middle ages also in that sense, in that sense of life, a phase in one’s life.

[2] Editor's note: AAVV (COHEN, Jerome; WHEELER, Bonnie, eds.), Becoming Male in the Middle Ages, 1997.

[3] Editor's note: HARTNELL, Jack, Medieval Bodies: Life and Death in the Middle Ages, 2018.