– 26.05.2019

“The last trace of the wounds made invisible by cultural-political decisions”, the photographs of Stefano Serafin, taken 100 years ago in the aftermath of what became known as the First World War (1914-1918), are the focus of this exhibition at the Avenida da Índia Gallery (Municipal Galleries / EGEAC), curated and researched by Paula Pinto, author of the doctoral thesis Condemned to Invisibility? Antonio Canova and the Impact of Photographic Reproduction on the History of Art (2016). The exhibition invites us to reflect on trauma, memory, invisibility, processes of the construction and reconstruction of History and on the complexity and challenges inherent in contemporary approaches to images that document the destruction of objects. In revealing the lapses, failures and wounds of war, we come to an understanding of what James Baldwin meant when he wrote, quoting James Joyce: ‘History is a nightmare from which I am struggling to awaken. We have all heard what happened to those who slept too long.’

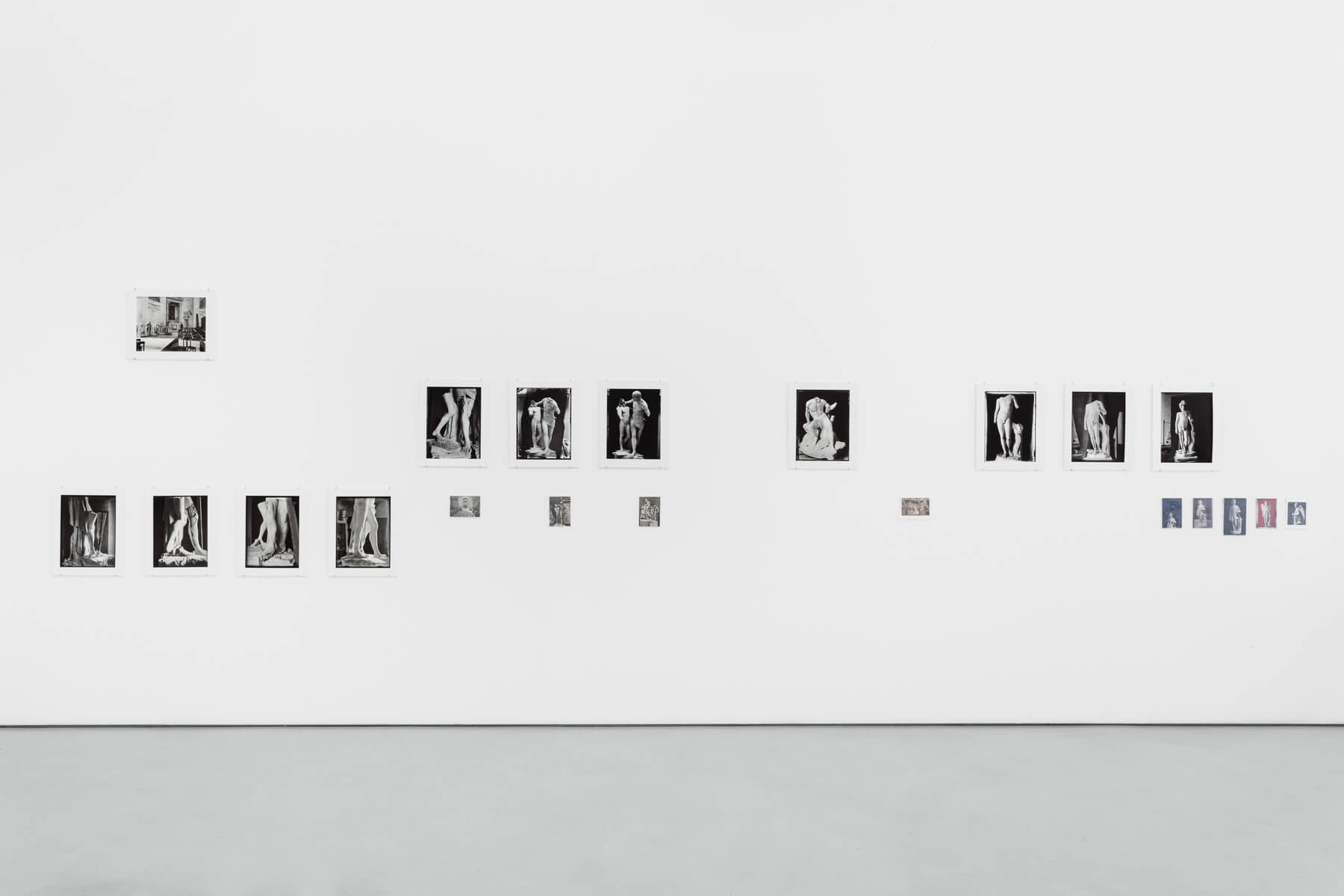

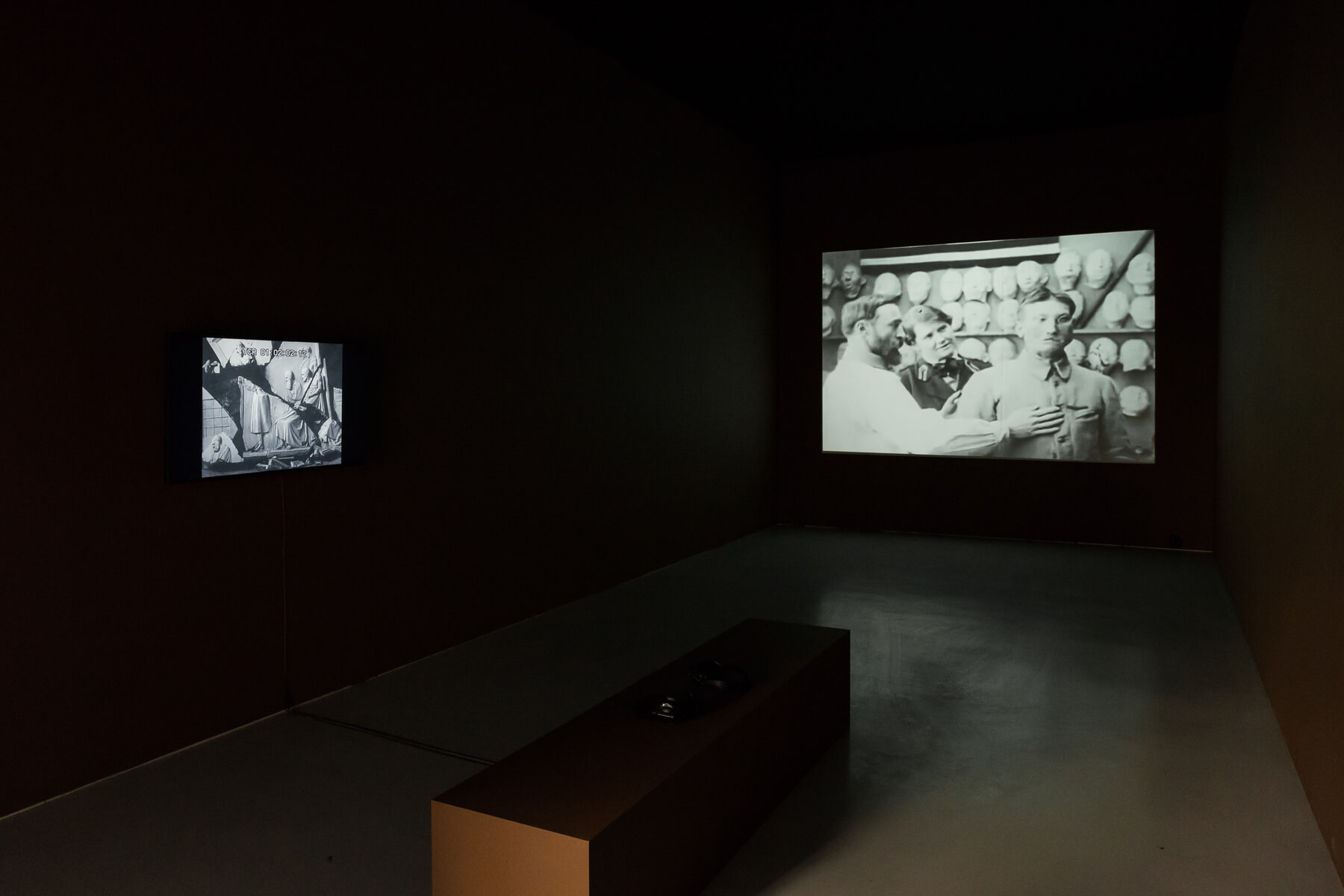

The photographs of Stefano Serafin (Possagno, Veneto, 1862-1944), which depict Antonio Canova’s (Possagno, 1757-1822) sculptures after they were severely damaged in 1917 in the midst of World War I, have had a major impact on the history of photographic reproduction of artworks and on the history of the objects themselves. His photographs demonstrate the extreme destruction to which these artworks were subjected and as a result no longer represent Canova’s original sculptures. Stefano Serafin – who had served as the curator of the Gipsoteca (Plaster Cast Gallery) since 1891 – subsequently reconstructed the original works. This made it necessary to view these objects not so much as individual artefacts but rather as objects that had undergone transformations. By invoking the various phases of Canova’s creative process, which led to the production of the various plaster reproductions stored in the Gipsoteca in Possagno (Veneto), Serafin was able to reconstruct most of the plaster casts with the aid of their corresponding marble sculptures. By making moulds of the marble works to recover the plasters, Serafin reversed the hierarchy of these objects, transforming some of the original models into copies. Yet these inversions highlight the complexity of the reproductive processes used by Canova which remain absent from the modern perception of art objects as unique and original objects.

Often dismissed as a “non-interpretative” means of reproduction, photographs of works of art, a bit like plaster casts of three-dimensional works, were ironically appropriated by the copy museums due to their understanding as a self-effacing medium; it was their supposedly self-effacing visual and material condition that allowed these reproductive objects to be considered as “genuine”. In contrast, Serafin’s photographs captured the “aura” of Canova’s original plaster casts. Although the idea of facsimile plays a central role in the technology of reproducing plaster casts, the restoration process made it possible to more clearly identify the transformative processes undertaken on the artworks. Serafin’s restorations thus helped regain the sense of mastery within the tradition of sculpture, which had been lost precisely because of accessing works of art via photographic reproductions.

However, in this specific case, rather than being destroyed, these plaster casts gained an autonomous existence. Serafin’s photographs are not authorial works, and they certainly do not aim to perpetuate the brutality of war. Instead, they reveal the capacity of the photographic medium for invention. The essential capacity of photography – which is also a reproductive art – is to distance itself from the artwork itself and document the work in the specific manner in which it is found in a certain time and space. From its origins, photography has been seen as a means of preserving artworks from destruction. Serafin’s photographs, in contrast, are more like the portrait of Dorian Gray, growing older while their subject – the plasters – maintain their original appearance thanks to successive restorations. Due to their documentary value, the museum kept these photographs under lock and key. Some of Stefano Serafin’s glass negatives survived the perils of World War II and the neglect that resulted from generalised institutional disinterest for photographic reproduction. Today the glass negatives are reaching their physical limits of survival, but they are the last material records of Antonio Canova’s original plaster casts. Their value as images reveal the historical processes normally concealed by a work of art.

These images reveal the torture of war and the dedication with which Stefano Serafin restored the neoclassical beauty of Antonio Canova’s art, highlighting the ruins through which we seek to give meaning to life, in an imbalance between the obligation to rebuild memory and the expectation that art, unlike everything else, will survive intact forever.”

-Paula Pinto, Curator

– 26.05.2019