– 23.09.2018

Municipal Galleries are pleased to present Alice dos Reis’ first solo exhibition, Pálpembrana, curated by Sara Antónia Matos and Pedro Faro, in the Boavista Gallery. It is the latest in a series of solo exhibitions in this space by emerging artists in the context of Portuguese contemporary art. This series began with João Gabriel, at the beginning of 2018, and Alice dos Reis will be followed by Maria Trabulo (October – December 2018), Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela (January – March 2019) and Sara Chang Yan (June – September 2019).

This exhibition by Alice dos Reis, which includes various sculptures, installations and two films, comes from the line of inquiry and reflection recently developed by the artist in her master’s thesis ‘Slimy Fillings’, carried out in the Netherlands, which will be available as a booklet at the exhibition. In this research, the artist expands on the growing impact of the ‘cute’ aesthetic in contemporary Western semiotics. Alice dos Reis’ thesis and the work she is exhibiting attempts to analyse the relationship between the ‘cute’, or things considered to be ‘cute’, and ideas about power and oppression, thereby investigating the intersection of the aesthetic with new technologies, online interactions, politics of gender, vigilance and work, ultimately proposing ‘cuteness’, as a radical aesthetic. Essentially, Alice dos Reis uses as her conceptual basis an idea that attempts to modernize the aesthetic theory around new categories – alternatives to traditional analyses of the beautiful and the sublime –, which relate to the social activities, objects and products generated by late capitalism, that saturate its cultural universe – see Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting, by Sianne Ngai. Affection and emotion, language and communication, intimacy and attention infiltrate the way we look at History, triviality, style, and the judgement that we make about things.

The film Mood Keep, the central piece of this exhibition, is based on the figure of the Mexican axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), ‘a long, cylindrical salamander, reaching lengths of about 30 centimeters (12 inches). A neotenic salamander, its most notable physical feature is its gills, which protrude from the back of its wide head and remain there throughout adulthood.’ [1]. It is critically endangered due to the illegal trade of exotic species and the constant destruction of its habitat, caused by the spread of human occupation, in particular the fatal draining of Lake Xochimilco by Spanish colonists in the 16th century. The axolotl has very particular regenerative qualities and does not complete metamorphosis. The salamander therefore maintains a larval appearance even in its adult state (neoteny). The axolotl’s skin is dark and often spotted. Albino individuals are common. The species is exclusively aquatic throughout the whole of its life cycle. Due to its high capacity for tissue regeneration, the species has been widely bred in captivity, especially for scientific research.

The film Mood Keep reflects on the intersections between the post-colonial history of the axolotl, its unique – almost supernatural – biological form and existence and its recent online popularity, where it is considered to be one of the cutest creatures in the world. Behind their cute exterior, they are ferocious predators and, when left in enclosed spaces with a high population density, they become cannibals. The figure of the axolotl, according to the artist, thus fuses ideas of alterity and non-patriarchal practices of empathy and connection between human beings and non-humans. In the film’s narrative, these cute creatures communicate with each other via Wi-Fi and watch cartoons that are digitally generated by telepathy. The axolotl, almost blind, is only capable of distinguishing between light and shadow, so the constant glare of incandescent lighting in the aquariums where they are bred is unpleasant and disrupts their ability to communicate. Collectively, in captivity, axolotls can develop eyelids, opting to close their eyes indefinitely in order to recover their command over their bodies and to stimulate empathetic communication between one another.

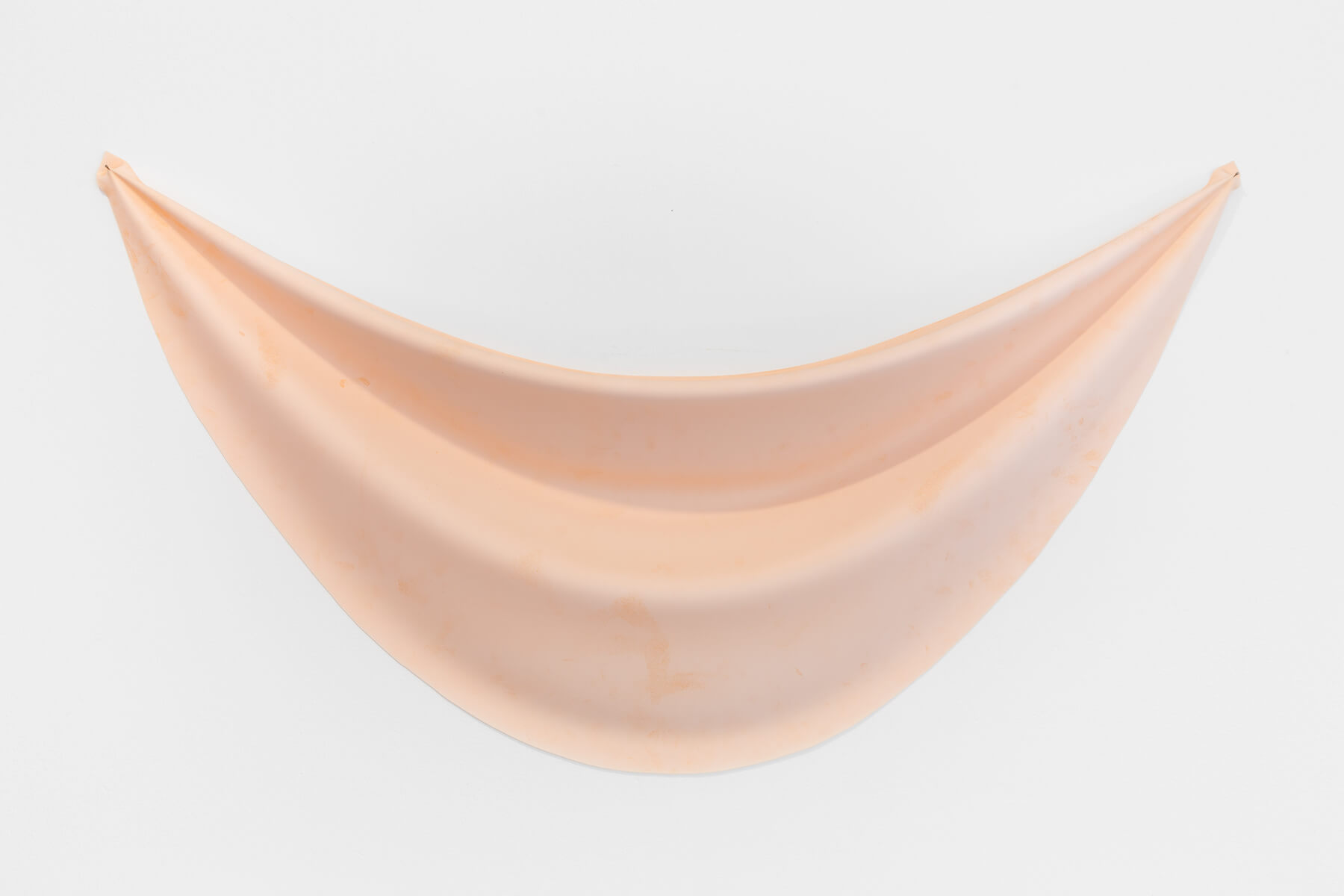

The title of the exhibition, Pálpembrana, is a play on words, merging the Portuguese words for ‘eyelid’ and ‘membrane’. One of the etymological origins of the Portuguese word pálpebra, – eyelid, in English – comes from the Latin verb palpare, which means ‘to touch’ or ‘to gently tap’. Anatomically, the eyelid is considered a membrane. For membrane, dictionaries offer the following definition: ‘A thin sheet of tissue or layer of cells acting as a boundary, lining, or partition in an organism’ [2]. In the film Mood Keep, the axolotls – creatures covered in membranes – develop eyelid-membranes which allow them to close their eyes. Other pieces on display in the exhibition, in latex – the texture of which could be considered ‘membranal’ – and in acrylic, examine and play with the idea and form of the eyelid: is it an eyelid or a smile (emoticon)? Alice dos Reis attempts to connect this set of ideas with the dimension of the gaze, and with the scope of what is ‘cute’, of touching and caressing: palpare.

Ultimately, we can think of ‘pálpembrana’ as the formless, gelatinous and slimy structure that enables the relationship between all these things, which glues them together, covering, touching and distributing them in a disruptively amusing, idiosyncratic and unconventional way. ‘The pálpembrana is similar to the web-like forms which we begin to see when we close our eyes to the light’ – says Alice dos Reis, thus questioning the function of art in the era of digital globalisation, attacking its current methods of contemplation and production, by exposing the paradoxes of the status of art at the heart of a context of globalisation, taking into account its different economic, political, visual and cultural circumstances. Can art think of what is odd, bizarre/strange and amusing?

– Sara Antónia Matos and Pedro Faro

[1] – Axolotl in Encyclopedia of Life [Consulted online 2018-07-10 17:52:32]. http://eol.org/pages/1019571/details

[2] – Oxford Dictionary of English [Consulted online 2018-07-10 19:25:07]. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/membrane

– 23.09.2018