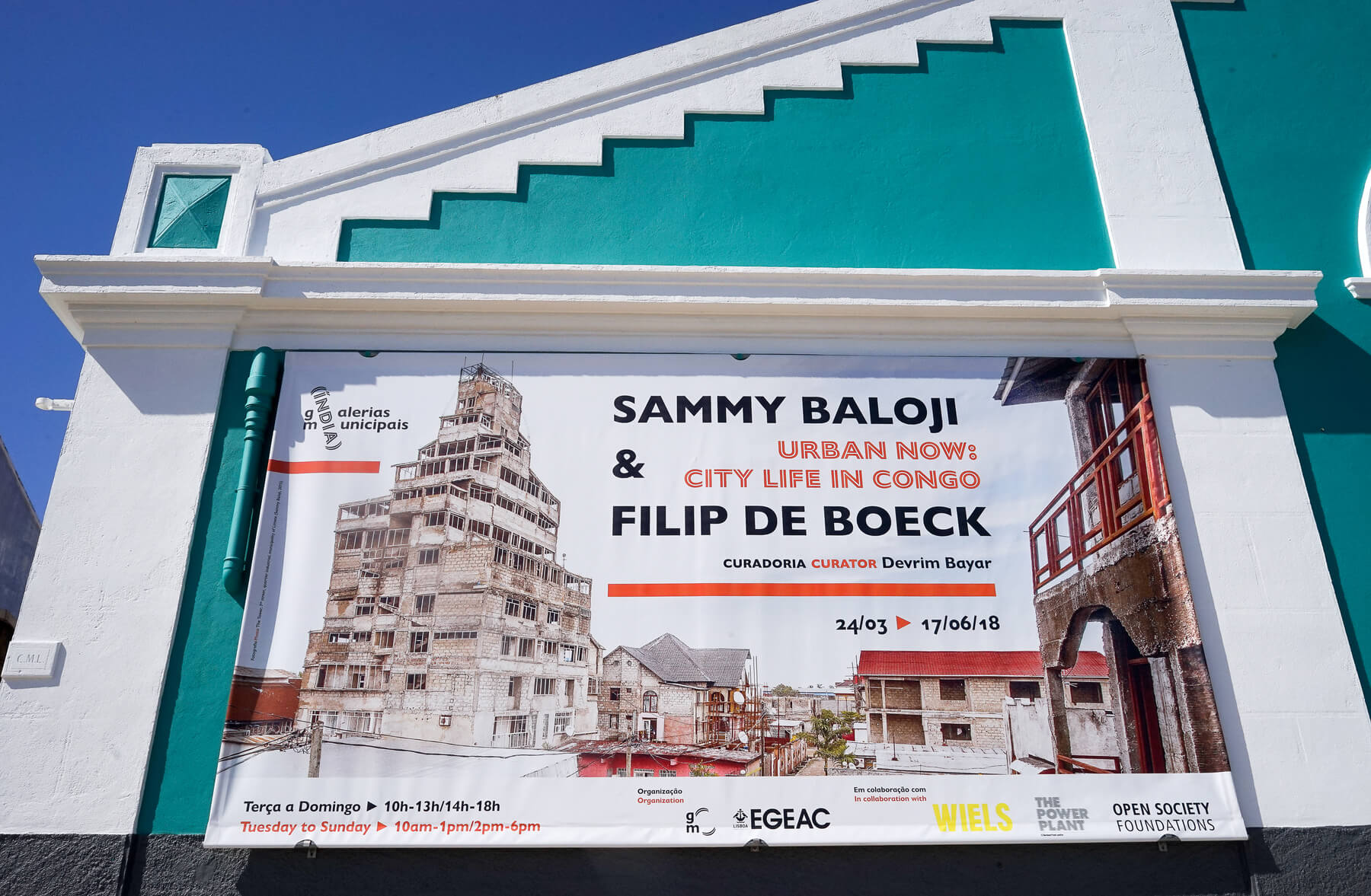

– 17.06.2018

In ongoing discussions about the nature of the African city, architects, urban planners, sociologists, anthropologists and demographers, devote a lot of attention to the built form and to the city’s material infrastructure. Architecture has become a central issue in western discourse and in wider reflections on how to plan, engineer, sanitize and transform the urban site and its public spaces. Mirroring that discourse, architecture has also started to occupy an increasingly important place in attempts to come to terms with the specificities of the African urbanscape and to imagine new urban paradigms for the African city of the future. Very often these new urban futures manifest themselves in the form of billboards and advertisements. Through an aesthetic display of modernization as spectacle, inspired by urban models from Dubai and other recent urban hotspots from the Global South, these images foster new dreams and hopes, even though the cities they propose invariably give rise to new geographies of exclusion, as they often take the form of gated communities and luxury satellite towns for a (hypothetical) local upper middle class.

In sharp contrast with these neoliberal re-codings of earlier colonialist modernities, the current infrastructure of Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is of a rather different kind. The built colonial legacy has largely fallen into disrepair. Its functioning is punctuated by constant breakdown, and the city is replete with disconnected infrastructural fragments, figments, reminders and echoes of a former modernity that continues to exist in a shattered form but without its original the material and conceptual content. These fragments are embedded in other historical rhythms and temporalities, in totally different layers of infrastructure and social networks. Failing material infrastructures and an economy of scarcity now physically delineate the limits of the possible in the city, but simultaneously they also generate other possibilities and enable the creation of new social spaces whereby breakdown and exclusion are bypassed and overcome.

The exhibition reflects on these diverse narratives of urban place-making. It offers a visual study of things that defy verbal narration: the city’s affective landscapes and moods. As such, the exhibition considers changes in how cities and territories are imagined by different kinds of people in the DRC today.

The ethnographic, photographic, and filmic exploration of the cityscape that visual artist Sammy Baloji and anthropologist Filip De Boeck propose, offers an investigation into the qualities of the ‘hole’. Today, the notion of the hole (libulu in Lingala, the lingua franca in large parts of Congo) could be said to fully capture the essence of the Congolese city’s material quality. It defines the generic form of Congo’s postcolonial urban infrastructure. Indeed, the surface of the Congolese city is pockmarked with potholes, while unstoppable erosion points constantly eat away at the urban tissue. Similarly, the surface of the Congolese landscape is disfigured by artisanal mining holes and the holes of (often unmarked) graves. In fact, the concept of the ‘hole’ has become a kind of metaconcept that people use to reflect upon the material degradation of the city’s colonial modernist infrastructure and to rework the closures and often dismal quality of the social life that has followed the material ruination of the colonial city.

What this exhibition reflects upon, then, are the questions of how this ‘reworking’ is taking place and how this postcolonial hole is being filled in the experience of Congolese urban residents. What possible answers does urban Congo propose in response to the challenge posed by the hole? If the city has transformed into a hole, how can this hole be ‘illuminated’ to become something that enables living, and living together in the city? For the makers of this exhibition, the notion of living together can only exist where the whole, the assemblage, is not fully formed and is not yet closed. For, living together always implies a contestation about how a social body, a collective, completes itself – it is a process that is never completely closed, summed up, or fully identical with itself.

As family, kinship, and neighbourhood solidarities are often stretched to the limit, and residents search sometimes desperately for a viable experience of being together, the makers of this exhibition try to trace what new forms are emerging, and how to understand these new forms. What is investigated here are the closures and openings through which this living together in the city is made possible or rendered impossible. In this sense, the exhibition can be read as an attempt to discover where and how people stitch their lacks and losses together and suture the folds, gaps, and holes of the city. Sutures here suggest the possibility of closing wounds, generating realignments and opening up alternatives, thereby also pointing to new kinds of creativity with (spatial and temporal) beginnings, and new forms of interactivity and conviviality.

Baloji and De Boeck investigate these gaps and sutures by means of a number of urban acupuncture points, in other words, investigations of specific sites within (and often beyond) the city of Kinshasa – particular buildings, horticultural sites and fields in the city, specific graveyards, mountains, potholes, new city extensions, and so on – into which they stick their analytical needle in order to understand what is happening in all of these places that form important, though sometimes barely materially visible, nodes within the city. These sites are where the city switches on and off, where quickenings and thickenings of goods, people, and publics are generated and the various lines and connections between them become visible.

The Tower

One of the early landmarks of Belgian colonial urban architecture in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) was the Forescom tower. Built in 1946, it was city’s first skyscraper, and one of the first high rise buildings in Central Africa. Pointing towards the sky, it also pointed to the future. It embodied and made tangible new ideas of possible futures, and as such the tower materially translated emblematically visualised colonialist ideologies of progress and modernity.

Today, a stark contrast to the Forescom Tower can be found in the municipality of Limete. Conceived, realized, and owned by the “Docteur,” a man who introduces himself as a “doctor in aeronautics and spatial medicine,” this still unfinished tower has been under construction since 2003, without the help of professional architects. This postcolonial tower challenges the 1946 Forescom building and everything it exemplified at the time, while illustrating the various ways in which the colonialist legacy continues to be reformulated and reassembled today. The video featured in this exhibition, titled The Tower: A Concrete Utopia, offers a guided tour of this remarkable tower by the “Docteur.”

The OCPT Building

Cielux OCPT (Office Congolais de Poste et Télécommunication), colloquially known as ‘the Building’ (le Bâtiment), is located in the neighbourhood of Sans Fil (‘Wireless’), in the populous municipality of Masina, east of the colonial heart of the city. The Cielux site was constructed in the mid-1950s as one of many branches of the major post office in the central downtown municipality of Gombe. A grand modernist, L-shaped building situated in a large walled compound, it housed a section of the national radio and functioned as an outgoing relay station for international telephone and telegraph communications (hence the neighbourhood’s name, ‘Wireless’). When it served this purpose, the Building literally connected Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) to the outside world, even though the site lay outside the city at the time of its construction. Today, the Building is occupied by several families, totaling more than 300 people. Most of them are still officially employed by the OCPT. In fact, the Ministry of Telecommunications has allowed some of its employees to move into the Building, as an advance for unpaid salaries or as a type of pension provision for retiring employees.

The Cemetery

The cemetery of Kintambo is one of the oldest and largest cemeteries of Kinshasa. Over the years, the city has increasingly invaded the cemetery, and informal settlements have sprung up alongside it. One of these settlements is Camp Luka, also known as ‘the State’. Here, the living and dead exist in close proximity. Although the cemetery was officially closed by urban authorities and abandoned in the late 1980s, the people from Camp Luka and other areas in Kinshasa continue to go there to bury their dead.

La Cité du Fleuve and the Vegetable Gardens of the Malebo Pool

Since the end of the colonial period, the south of Malebo Pool’s – a lake-like expansion of the lower Congo River between the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of the Congo – has steadily transformed into a vast agricultural zone. In the 1980s, a South Korean agricultural company started to develop rice paddies there, but this project was abandoned after the widespread looting that hit Kinshasa in 1991 and 1993. After the Korean company left, local residents quickly moved in to occupy the rice fields. Before long, they started to expand them, often using shovels or bare hands to fill in and reclaim the pool’s marshes.

A large portion of this vast agricultural space will now have to make way for the development of a new satellite city, the Cité du Fleuve, a private development that started in 2008. Built on two artificially created islands in the Malebo Pool, the Cité du Fleuve will be 6 kms2 in size, and include over 200 villas and 10,000 luxury apartments, 10,000 offices, a marina, schools, cinemas, restaurants, and conference rooms. It will be connected to the rest of Kinshasa by two bridges and a transit road. Self-sufficient in water and electricity supply, the Cité du Fleuve is promoted as offering potential buyers a luxurious lifestyle and secure land titles.

Maquette of Kinkole City

Kinkole City is one of the last fully planned zones of Kinshasa. The plan was partly implemented in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Today the maquette gathers dust in a corridor of the municipal house of Nsele.

Land Chiefs

Land chiefs still control large tracts of land, particularly in the more rural parts of Kinshasa province to the southwest of the city in the urban districts of Lukunga, Funa, and Mont Hamba, and to the east in the urban district of Tshangu as well as on the Bateke Plateau. In Kinshasa’s eastern periphery along the Malebo Pool – a lake-like expansion of the lower Congo River between the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of the Congo – important Teke and Banfunu chiefs have been reigning over the same vast areas of land that their ancestors had controlled when Welsh journalist and colonial explorer Henry Stanley arrived and started exploring the region in the 1870s. It is no coincidence that these areas of the city are the ones now undergoing expansion. In this process of rapid urban growth, these land chiefs play a decisive role, even though their administrative function is often not recognized by state institutions. It is simply impossible for an individual, a real estate company, or an industrial investor to obtain a piece of land without first negotiations with them.

Fungurume / Pungulume

The town of Fungurume is in the province of Katanga, between the large mining centres of Kolwezi and Likasi. Home to the Sanga people, Fungurume is surrounded by hills and mountains that form one of the world’s largest copper and cobalt deposits. These mineral resources remain largely unexploited. People have always engaged in artisanal mining here, and in pre-colonial times, the area was a major centre in a continental copper trading network. Large-scale industrial surface mining is more recent. In the mid-1990s, during the final years of President Mobutu Sese Seko’s reign, the Canadian Swedish Lundin Group obtained concessionary rights from the government to mine most of the mountains around Fungurume, an area of 1500 kms², but it was not until 2006 and a major change in the holding company’s ownership structure that Tenke Fungurume Mining consortium started up its open-pit and oxide ore processing facilities. Between 2009 and 2015, the consortium was mining multiple deposits concession-wide. The company also started to plan for the construction of a whole new city, an airport, labor camps for the workers, large processing plants, and a number of other industrial facilities. The construction of this new infrastructure would necessitate the further relocation of some 15,000 local Sanga residents, including the Sanga chief, Mpala Swanage Pascal Musenge. In May 2016, however, the Tenke Fungurume Mining consortium unexpectedly changed hands, when China Molybdenum bought the shares of the American group FreeportMcMoran for $2.6 billion. It is not certain at this point whether China Molybdenum will implement the new infrastructure project.

– Devrim Bayar, curator

– 17.06.2018