Interview in the scope of ‘Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti’ by Cecilia Eliceche & Leandro Nerefuh

Daniel Peres: Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti looks at the cultural multiverse, as it were, of Abya Yala[1]. It focuses especially on Haiti, where politics and spirituality have been closely linked, specifically in the context of the anti-colonial and anti-slavery revolution of 1791–1804, considered the first insurrection for an independent abolitionist state. It is particularly interesting to think about the potential links between Haitian resistance and Vodou cults, including the artistic expressions – visual, musical and performative – that they involve.

With the historical and cultural context of Haiti as a backdrop, would you like to comment on these conjunctions of politics, spirituality and art and how they show up in this project? What do they tell us about the emancipations and empowerments that need to take place today?

Leandro Neferuh: Good morning. We are very grateful for this opportunity to expand the conversation. During our research for the work HAITI o AYITI, we were very impressed by the story of Bwa Kayiman, which was a multiple event in space and time, a mix of political assembly, war council, dance congress, ceremony and ritual offerings, systematically planned for four years, and carried out in August 1791. Bwa Kayiman wasn’t just the genesis of the victorious Haitian revolution, but also of Haitian Vodou and the Kreyòl language. Imagine the expansion of horizons (philosophical, technological, aesthetic) this entailed, in a context of slavery and colonialism as the norm of the modern world. Today, Bwa Kayiman is still commemorated (relived) every year and conveys a highly affirmative, creative, abolitionist and inclusive energy, whose central axis is the question of universal freedom as the very definition of humanity. Tout Moun Se Moun. All people are people. Whether they be human, stone, plant, water or animal. Humbly, we can say that our work is a tiny contribution to the maintenance of this environmental programme that is Bwa Kayiman.

Installation view of part of Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (First floor); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

DP: The ecological vector is fundamental in your proposal, emphasising how bridges between nature, religion, society and art have long been present in many of the cultures you study. You compare these primordial environmentalisms, so to speak, with contemporaneity and often adopt a posture of protest, which comes across very clearly in the booklet you distribute at your exhibition in Lisbon. In it you describe a global order of domination, based on something that, in a text for Umbigo magazine about this project, José Pardal Pina referred to as ‘the four horsemen of the modern apocalypse: climate change; colonialism; capitalism and patriarchy’[2].

Could you talk a bit more about how your project invites the public – each subject – to feel environmental urgencies that are also, simultaneously, spiritual and political? These are invitations for reflection that are sometimes very different from those that emerge in contexts like history, ethnology and anthropology. Is there anything you’d like to say about this differentiation?

LN: We borrow here a reflection from Weichafe Mapuche Moira Ivana Millan, who says: ‘Instead of thinking about what planet we are going to leave for our children, we should think about what children we are going to leave for the planet.’ This call to action, which originated in Patagonia, echoes Haitian Vodou, in the principle ‘Bati moun nan pou n ka pwoteje plánet nou an’, which roughly translates as ‘building people (building good character) capable of protecting our planet’. This says a lot about the radical difference between what you called primordial environmentalisms and the Western belief in the modern scientific paradigm. These primordial environmentalisms that vibrate across Abya Yala (like in Haitian Vodou, for example) are at the same time ancient and current/contemporary. To be human means to build a relationship of reciprocity and kinship with the earth. And art has a lot to do with this, with this aim of establishing the eternal return to the earth. This is the political, philosophical, spiritual, technological, in short, environmental function of sacred art.

Libidiunga Commons; ALTAR AYITI and ALTAR CABOCLO [detail]; Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (First floor); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

DP: Haitian culture is also made up of migrations – a factor whose extreme cultural, social, political and economic significance goes back to transatlantic slave trade and the African diaspora that derived from it. After liberation from the colonial yoke, migration remained central in other senses, spanning modernity, political dictatorship and now affirming its importance in the face of the violent economic situation. Migration is, in fact, a trait that the Haitian people share with others who have been subjected to colonial rule and the geopolitical stagnation that followed. Slavery and colonialism, imposing forced movements of people, gave rise to the miscegenation of cultures, many of them conceived in Africa and which mixed either with one another, or with native cultures, or the colonisers. This resulted in intercultural realities with their own belief systems, cosmologies and cosmogonies, often in religious syncretism. This intercultural matrix was later strengthened by new migrations, and so on and so forth. Although very different from one another, the socio-cultural complexes that resulted from this immense mixture can share deep roots. I’m thinking about the relationships between Vodou and Candomblé cults, both discussed on your site haitioayiti.com (see the testimony of Egbomi Nancy de Souza about Oxumarê, among other entries we found there), or with other religious realities that we could mention here, like Santería, for example.

Would you like to give us some of your thoughts about these intercultural (and intercultual) exchanges? What importance do you attribute to them and how do they present themselves in this project? In the religions and symbologies that you have studied and experienced, what common links and what differences would you draw attention to in their visual and musical expressions, dances, ritualised objects, sacred places, etc.?

LN: Of course, our work seeks historical connections that span Abya Yala, to show that territories can’t be isolated, even when they are cut up and torn apart by a modern colonial cartography, as has been the case during these past 500 or so years (from 1492 to today). History doesn’t follow a causal temporal linearity, past-present-future, regardless of whether this be a ‘modern scientific’ or a messianic path. The Afro-diasporic and indigenous cosmogonies of Abya Yala are diverse and extremely specific; at the same time, we can say that they’re informed by a very sophisticated understanding of space-time, of the comings and goings of humans on this planet, of the earth, and the universe, and of the responsibility of each of us in relation to this great collectivity.

The environment we created in Lisbon makes multiple references to these connections, beginning with POTO-MITAN, the vertical axis that intersects the floor/ceiling and joins the two floors of the gallery. It is the metaphysical axis that joins dimensions, the depths of the waters (the ground floor) with the dimension of the invisible (the first floor). On the first floor, we have an L-shaped table that forms a dual altar, for Ayiti and for the Caboclos of Brazil, like a kind of tribute to the strength of native populations in general. For some Afro-Brazilian religious anthologies, Caboclos are the original owners of the land and forests. In Haiti, we also find this reference (or rather, reverence) in the choice of the country’s name itself. As a colony, the territory was known as Saint-Domingue. After independence, in 1804, the island’s original name, AYITI, was readopted and resignified as a synonym of universal citizenship and freedom.

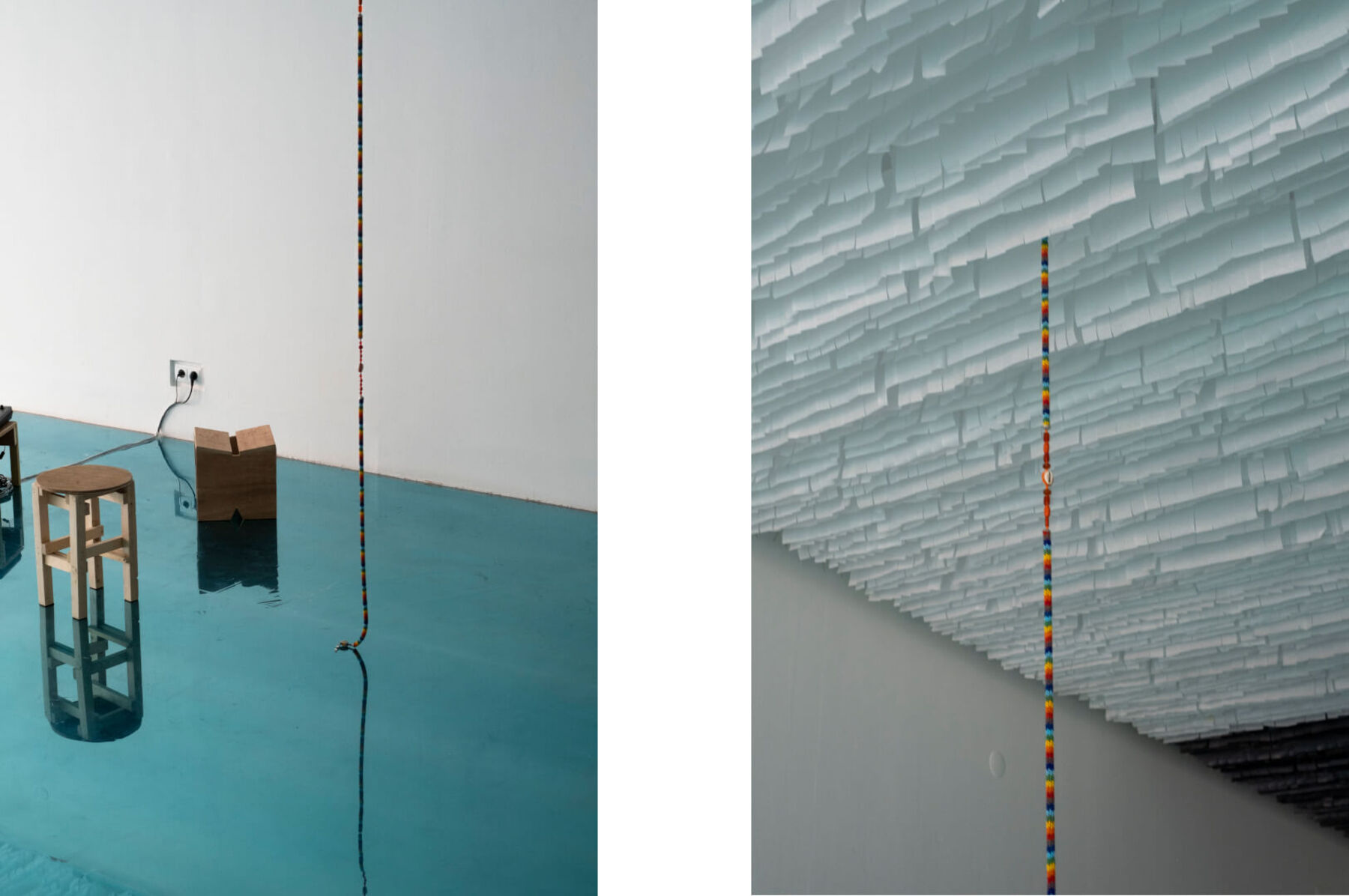

Libidiunga Commons; POTO-MITAN (2019) and BANQUINHOS CAIÇARA (2019–22) [details]; Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (Ground floor); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

Installation view of part of Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (First floor); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

DP: As we’ve already mentioned, migration and life in the diaspora still dominate the realities of many Haitian individuals and families. Communities abroad have important roles to play in the dissemination of Haiti’s history and culture – namely the Vodou religion, one of its structural features, and also in the clarification of widely held ‘Western’ projections. The Haitian community and its descendants in the United States of America, for example, are among those who we can most easily relate to from a distance – I’m referring, for example, to La Troupe Makandal’s journey from Port-Au-Prince to New York, developing the work of master Haitian percussionist Frisner Augustin (1942–2012) and the collaboration of New York ethnomusicologist Lois Wilcken (1949) – but there are many other groups around the world doing important things.

Do you maintain relationships with various communities of the Haitian diaspora? How is the significance of Haitian migration expressed today and how does it manifest in different societies across the world? What most stays the same and what is most different, especially regarding ritual and artistic expressions, and their intersections with everyday life?

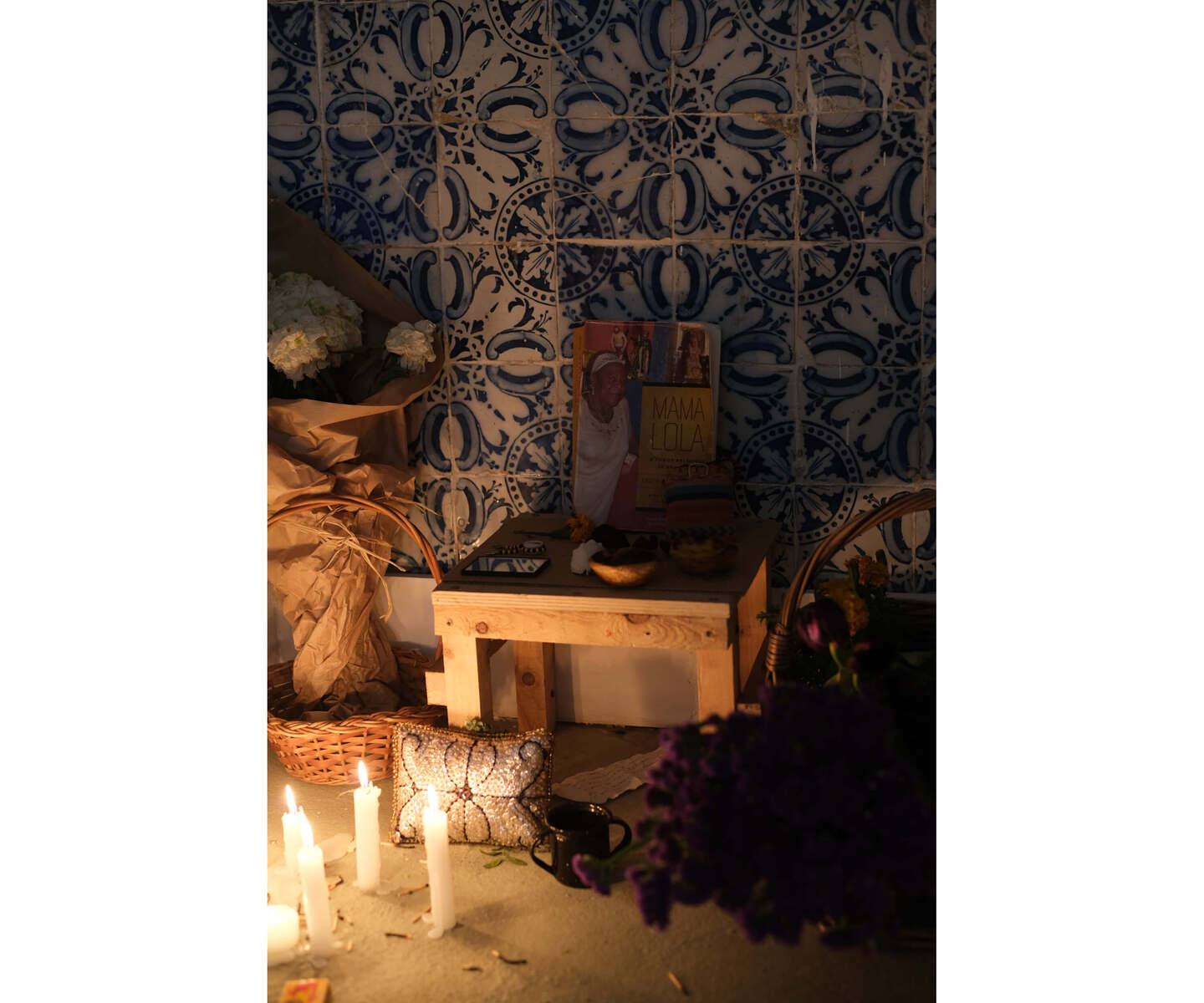

LN: Sorry, but we can’t answer such a complex question about Haitian migration in general. On the first floor of the Boavista Gallery, we put up a small altar for Mama Lola, on the day of the anniversary of her death. Mama Lola was a very important Manbo (a Haitian Vodou priestess) for the Haitian community of New York and its networks of relations on the East Coast of New York and beyond. We recommend her book, written together with anthropologist Karen McCarthy Brown, as a good example of the work of the Haitian diaspora connected to Vodou. The book is called Mama Lola, a Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn.

Libidiunga Commons; DANBALAH & AYIDA WEDO (2019); Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (Staircase); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

Altar para Mama Lola; Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (First floor); 2022. ©Luciano Cieza

DP: Your proposal recalls the unities between art and other spheres of individual and collective life – religion, nature, politics, society… Essentially, Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti brings us back to the fundamental ‘Art and Life’ debate (using one of the most common formulas to name this endless field of questioning), paying special attention to spirituality and to the intercultural paths that it has forged and continues to forge today.

With its ritualised objects, Ve-Ve (drawings dedicated to a specific spirit, or Iwa), performances (dance offerings to the mystic entities Yene, Lanalèn, Lasiren), has your initiative transformed the spaces and experience of the Boavista Gallery into a kind of ounfò (Vodou temple)? In the matters and immaterialities of your proposal, when does the poetic definitively mix with the effective belief in invoked supernatural spheres?

LN: The environment we created in the Boavista Gallery isn’t a sacred environment, just as the three offerings of dance we did in May and June weren’t ceremonies, despite having their own ritualistic connotations. Neither are they an artistic representation of something authentic that is separate from us (Cecilia, Leandro, collaborators). With the work presented in Lisbon, we are trying to establish an energetic-aesthetic-spiritual connection with some of the telluric and cosmic forces worshipped in Haitian Vodou, in our way, and at the same time in dialogue and with the permission of our mentors, Houngan Jean-Daniel Lafontant of Na-Ri-véH Temple in Port-au-Prince, and Egbomi Nancy de Souza, Senior Researcher of the Pierre Verger Foundation in Salvador, Bahia. We are learning with them about the sacred dimension of art, art which serves life in all its expressions and radical differences, art which has a concrete and material function of nourishing vital forces. We are learning that faith is fundamental to creation, whether in the strategy of an abolitionist revolution, or in a dance choreography.

In our work, the poetic is intrinsically linked to this question of faith and the ritualistic function of art. But we don’t consider Haitian Vodou as a belief in the supernatural. Not least because the supernatural is natural (look at quantum physics). Haitian Vodou is a method of building and organising societies based on communitarian principles that don’t depend on a bureaucracy of state control. What’s more, Vodou is a science, in which ‘art’ plays a central and creative role.

Dance offerings; Panamérica, lavro e dou fé! Ato 1 – Haiti o Ayiti; Galeria da Boavista (Entrance and Ground floor); 2022; dance (kulev yo) performed by Cecilia Lisa Eliceche, Admila Cardoso, Emily da Silva. ©Luciano Cieza

DP: Many of the pieces are attributed to Libidiunga Commons, including the booklet that accompanies the project.

Would you like to talk a little bit more about this authorial entity?

LN: Libidiunga Commons is a specific authorial license that applies to the joint work of Nerefuh with several collaborators. It was inspired by Yvypora Commons, a license created and disseminated by Paraguayan Guaraní poet Edgard Pou, based on a principle of anti-intellectual ownership, which also goes beyond attributions of creative commons and copyleft, for example. Libidiunga Commons is contextual, that is, designed for each specific context where works are circulated and disseminated, with the common basis of attributing ancestral, geographic, and historical sources, respecting secrets and the sacred, and taking responsibility to check sources and request permission from the guardians of knowledge. In the case of the work HAITI o AYITI, this meant working closely with Egbomi Nancy de Souza and Houngan Jean-Daniel Lafontant; composing and disseminating an authorial and anti-colonial narrative about Haiti and Vodou; and making materials available and talking to those who wish to learn more about the work.

DP: Haiti o Ayiti is presented as the first act of Panamérica, lavro e dou fé!, which leads me to ask:

Do you have more acts in the pipeline? What can you tell us about them?

LN: Yes, Ato 1 – HAITI o AYITI will at least be followed by Ato 2 – THE CORE, which will be about the inside of the earth, metals and the curse of mining and its demon – expressed in the danza diablada, and the smoke xawara; and Ato 3 – CRUZE DOS ANDES, EXHUMUS, which will be about the sacred mountains of the Andes and their stone elders, as well as their fossils and human cadavers. We expect to complete them both between 2022 and 2025.

[2] In https://umbigomagazine.com/en/blog/2022/07/05/panamerica-lavro-e-dou-fe-ato-1-haiti-o-ayiti/ (accessed on: 14/07/2022)