Interview around the exhibition “O Colecionador de Belas Artes” [The Fine Art Collector]

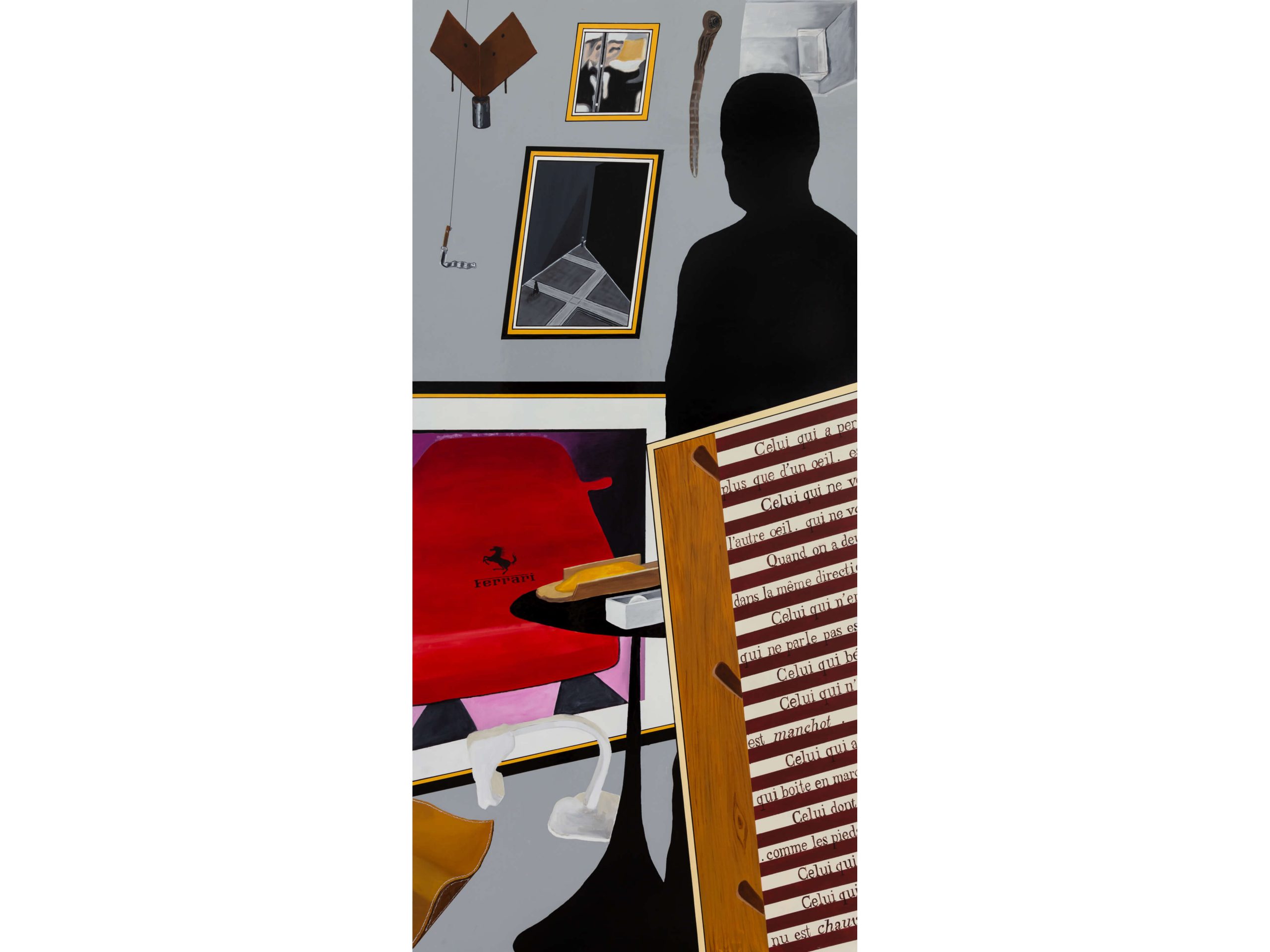

Held at Quadrum Gallery between April and June 2022, 27 paintings by Sara & André belonging to the series O Colecionador de Belas Artes [The Fine Art Collector] (2021–22) are presented to the public for the first time. Each piece involved conversations with private art collections and represents “the collector” in the presence of works from their collection, always presented anonymously as the same black silhouette the duo have appropriated from that used by António Areal in his series of paintings from 1970–71.

Installation view; Sara & André, O Colecionador de Belas Artes [The Fine Art Collector]; Galeria Quadrum; 2022. © Bruno Lopes

Daniel Peres: As we enter the gallery, the 27 paintings appear to stand independently, distributed neatly along the central part of the space and with their “backs” towards the entrance. We first come across the back of painting #1. As with the other pieces, it bears two labels: one identifies the artworks represented; the other contains the title, technique and dimensions of the painting, and your joint signature. If we wanted to start by seeing all the paintings front-on, we would have to go to the back of the gallery then walk around the room in reverse, from piece #27 to piece #1.

Looking first at the back of the paintings and their labels makes one think that you are emphasising the importance of the mechanisms of certification and authentication of artworks, that one must scrutinise them critically. On the other hand, installed vertically and with their backs to the entrance, the paintings seem to create a kind of surprise effect, a game of veiling and unveiling that may be related with the question of anonymity, which is important in your work.

Would you like to comment on the exhibition design and the perceptions that it elicits?

Sara & André: We tried out three different display models before deciding on this version, though all of them worked quite well. On the first day of assembly, we divided the paintings into two lines, the left line facing the front and the right line facing the back. This solution worked quite well formally, but it didn’t create as many relationships between the works and didn’t invite you to wander around the space or get closer up to the paintings, since they were all in a similar position.

On the second day we tried to distribute the paintings in the centre of the room in the position they ended up in, but facing the entrance. This solution was extremely aesthetic, but also not very effective as it didn’t compel the visitor to enter and/or go all the way to the end of the exhibition. On the third day we kept the same position we had fine-tuned the previous day, but reversed the orientation of the paintings, forcing the visitor to walk all the way through the space if they wanted to see all the paintings. At the time we feared this might seem a somewhat arrogant or gratuitous gesture, but we quickly realised that this version could provoke longer, more attentive engagement with the exhibition, so we opted for this version pretty much wholeheartedly.

It’s important to say that all these decisions were made in dialogue with Tobi (Maier, director of the Municipal Galleries) and with several other members of the Galleries’ staff who passed by every day and gave their opinions. From the first moment we showed the models of the paintings, about a year earlier, and mentioned that we were thinking of a possible two-line set-up, Tobi mentioned MASP (in São Paulo) as a possible reference for this set-up.[1] And that is exactly where we ended up, funnily enough.

Showing the back of the works was not intentional. As we say, this was the third mounting option. But we admit to having a great interest and curiosity in the back of the works in general. The backs are rarely visible, only available to the owners. Especially in the case of older works, they often provide another aspect of the history of the work, with references to fine arts stores, galleries and auction houses where the work has been bought and sold, other elements inserted by the artist, and sometimes identifying marks of the collections in which the work has been included. So perhaps our interest was somewhat unconsciously influenced by these aspects.

Finally, the solution of placing labels on the back of the paintings was to attain a certain economy of means, since if we included the information about all the works represented (inside the paintings) in the exhibition information sheet (around 160 works, if we are not mistaken), it would run to multiple pages and this is probably not information that most visitors want to take home with them.

Installation view; Sara & André, O Colecionador de Belas Artes [The Fine Art Collector]; Galeria Quadrum; 2022. © Bruno Lopes

DP: The display reinforces relationships with Quadrum’s glazed space, which has no interior walls, making it compatible with pieces raised off the floor. But beyond this dialogue with the architecture, we can also direct our thinking to other specific interactions with Quadrum and its history, such as the fact that the series deals with art collecting and the national art market, both very present in the gallery’s history when it was also a commercial space. It’s almost as if the gallery is revisited by this memory through the presentation of your series. Perhaps some of the collectors in question acquired pieces at Quadrum, or artists alluded to in the paintings made sales during exhibitions at the gallery.

Does reflecting on possible relations between the series and Quadrum and its history seem relevant to you? Also, would you be interested in revealing whether the gallery is part of the group of art spaces about which you are reportedly preparing a new work?

S&A: We think those relations are important to think about, but we are not really qualified to comment, since we have not experienced the gallery as a commercial space and have not had the opportunity to study its activity, so any opinion we could give would be based only on some stories or episodes we have heard about and wouldn’t be worth much.

When we were considering Quadrum (Tobi left open the possibility of presenting a project for one of the other Municipal Galleries), we first thought about its architectural or formal qualities, although it was also important that at least one of the collectors mentioned made some of their first purchases in the gallery, that it was here where Maria da Graça Carmona e Costa started her career, and that it was a place where many other Portuguese and international artists and other figures had passed through over a long time.

With regard to the physical and architectural aspects of the space, when we first had the idea of doing this project, even before we knew we were going to present it at Quadrum, we imagined the paintings on the wall, so the decision to show them “standing” came precisely from adapting the series to the characteristics of the space.

As far as the future work you mention is concerned, in which we will focus on exhibition spaces, yes, Galerias Municipais will be included in our research (all of them, if we are not mistaken). But that work will take a very different approach from the one we have presented here, and it does not yet have a confirmed date or place of exhibition.

DP: The selection of the artworks represented in each painting is obviously of central importance, since it is the result of choices, and choices mark out positions.

From what I have understood, you asked the representatives of each collection for a range of collected works of their preference and then negotiated which ones would appear in each painting.

Do you think the selections indicate something significant about the distribution of artists, movements or periods in Portuguese collections? What can you tell us about the criteria of these choices, both on your part and on the part of the collections themselves?

S&A: The process essentially involved asking each collector to indicate not less than 10 of their favourite works from their collection, at least one of which was a sculpture, and then we made our selection of six pieces (with slight variations) before we started painting. Our selection had primarily to do with issues of scale. As a general rule, the two works at the bottom are larger and the three at the top are smaller. In the Areal series, as we interpreted it, the scale of the sculpture did not have to be respected and we followed this premise. Colour, the overall harmony of the set and, whenever possible, a wider range of artists represented were also criteria. The process varied greatly across the different collectors, with some choosing the works represented in detail and others entrusting us with this task entirely or almost entirely.

It would thus be difficult to make an overall assessment or present any kind of statistics from this study since we did not secure the participation of all the “great” Portuguese collectors. And there is a somewhat unbalanced age distribution, in the sense that older collectors are overrepresented, reflecting a longer held approach and period of construction of each collection, which have sometimes already entered a phase of lower activity or even stagnation. In this respect, as far as we understand, most younger collectors are by nature more discreet, or have not yet had the time to become widely known in the art world. We also asked each collector to indicate the works they liked the most and not those which were “worth” more (even taking into account the various types of value that a work of art can assume), and we have the feeling that this request was quite well respected, so these choices always reveal more about the works’ emotional value than anything else.

Still, we thought it might be interesting, in response to your question, to count how many times each artist was selected for each of the paintings presented in the exhibition. Within this logic, the favourite artist of the collectors, represented in five paintings, is Ana Jotta. Lourdes Castro and Julião Sarmento are close behind her, appearing in four paintings. Almada Negreiros, Ângelo de Sousa, Eduardo Luiz, Joaquim Rodrigo, Nikias Skapinakis and Paula Rego each appear in three paintings. Finally, repeated in two paintings are Adriana Proganó, Amadeo de Sousa Cardoso, Ana Vidigal, António Palolo, Cabrita, Carlos Correia, Costa Pinheiro, Daisy Parris, Dominguez Alvarez, Fernando Calhau, João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva, João Pedro Vale (there is also a work by João Pedro Vale + Nuno Alexandre Ferreira), Joaquim Bravo, Jorge Martins, Jorge Molder, Jorge Pinheiro, Jorge Vieira, José Pedro Croft, Júlio Pomar, Lawrence Weiner, Paulo Nozolino, Rui Chafes and Sonia Delaunay. From those we were given to “choose” and ended up not including in more than one painting, we should mention at least Álvaro Lapa, Helena Almeida, Nadir Afonso and Vieira da Silva. Finally, an artist that we weren’t able to fit in any composition, for various reasons, but who was mentioned by more than one collector was Noé Sendas. And there are several other artists that we were surprised not to have mentioned to us. We are thinking of two women artists in particular, but we think it would be indiscreet to leave their names here.

Installation view; Sara & André, O Colecionador de Belas Artes [The Fine Art Collector]; Galeria Quadrum; 2022. © Bruno Lopes

DP: It’s interesting to imagine that some of the selected works might eventually form part of other collections in the future. From this perspective, your work will relate to the memory of collecting also become a record of a specific time and state of affairs.

What do you foresee resulting from this facet of the work, namely in the fields of art criticism and art history, and how do you think your project problematises this?

S&A: It’s funny, but we hadn’t thought about the possibility of the works represented changing owners, since they are the collectors’ favourite works and, as far as we could tell, they don’t regularly dispose of their works (quite the opposite, in the sense that they are regular buyers). So, trying to think in the longer term and assuming that most of the works represented are really important in the context of art, especially Portuguese art, but not only, it is kind of magical to imagine that we are contributing to the historiography of each work by assigning it an owner and/or location. However, we are keenly aware that it is only a moment that is crystallised, nothing more than that, so we wouldn’t venture to discuss the potential historical relevance that this project may take on in a more or less distant future.

What we can say is that we feel we are in a moment in which collectors are becoming very important in terms of the Portuguese context (a situation which was already a trend some years ago internationally, just as with curators some years before that). The only merit we would attribute to ourselves in terms of the ambition or historical relevance of this project is that we have managed (or at least tried) to follow these movements in the most comprehensive and complex way possible in our specific context.

In critical terms, we would only highlight the fact that it is a project developed by artists, something that is relatively unusual for projects of this scope with this type of theme, considering the merits and downsides that such an approach or perspective can bring, of course.

DP: Painting #15 is 20 cm wider than the others. In an exhibition visit guided by you, it was mentioned that the increase in size is something that also occurs in one of the paintings of the series by António Areal (precisely the 15th and last piece, according to you). You also revealed that, in the case of your series, this increase in width ended up being allied to the fact that the collector in question had chosen a larger number of works that he wanted to be part of the composition.

Could you comment on this and other vicissitudes of the working process? How were they articulated with your appropriation and interpretation of the Areal series?

S&A: Of course. We would mention two or three factors beforehand. When we adopt works from other artists, as is the case of the original Areal series, we can take a more or less rigid approach in terms of respecting the original’s formal, technical, conceptual or other aspects. In this specific case, our approach was quite free. For example if we had done only fifteen paintings, we would have left out twelve collectors, but we considered that these twelve were fundamental to revealing the complexity and the different ways to build a collection (and this number may still grow when the book is published). Another important aspect in this kind of project is that when we invite people to work with us (and this is true for many of our works and/or series of works), we need to know how to listen and respect them, otherwise we would just be enforcing a previously held viewpoint, when what we want is precisely to be able to learn and discover with these people the very result of each research.

So, revealing a little of the process of working with each collector, the case of Pedro Álvares Ribeiro (painting #15 – a collection known as the Peter Meeker Collection) from Porto is actually interesting. He told us that it was impossible to choose only six works to represent his collection. He told us very clearly that twelve works had to be represented, that he knew it would be difficult, but that we would certainly manage because it was the only possible option. We like this kind of challenge and/or contingency, so after some reflection, we remembered that the 15th painting of the original series was 20 cm wider and so we decided to adapt this format to this collection so we could fit the twelve works in a quite acceptable way (to our eyes) in such a small space.

Another case is that of the Manuel de Brito collection, which is now held by Arlete Alves da Silva and Rui Brito, who play strong and distinct roles in the collection and asked us to paint a picture with the selection of each of them (pictures #16 and #22, respectively). These are the two most particular situations, but no doubt there would be at least two or three other interesting episodes we could mention (but won’t, for fear of extending our answers too much).

Sara & André; O Colecionador #15 [The Collector #15]; 2022. © Bruno Lopes

DP: The issue of anonymity appears with some élan in the context of this project (mainly during the exhibition), but afterwards it seems to be somewhat reduced through the book you have in preparation, which reveals who is “behind the black silhouettes” through interviews. Despite this, the idea of incognito is still a poetic attribute, working not only as a kind of enhancer of mystery, but perhaps even as a more “sociological” variable, insofar as the use or non-use of anonymity (with the myriad of reasons why one chooses it or not) is a characteristic feature of collecting.

What would you say about the issue of anonymity in this project and how you managed, anticipated, and contextualised it during the conception of the series and this first public presentation?

S&A: There are two important aspects to mention. First, we realised that several of the collectors, those who are not “well known” did not feel very comfortable revealing their names in the context of the exhibition and so we agreed that this reserve or discretion should be the exhibition baseline. We also thought it would be more interesting and provoke more discussion among visitors, friends and colleagues than just offering that information up front. We feel the visitor should participate in the exhibition in some way. As has long been known, it is the visitor who completes or ends the work, and this was the participation (or one of the participations) that we reserved for the visitor on this occasion. In parallel, we realised that, as far as the book is concerned, which we are now starting to prepare, many of these more reserved collectors would no longer be so reluctant to reveal their identities and that is why we decided to proceed this way, revealing only “who’s who” in the book. During the guided tours of the exhibition, however, this information was made available, and at the opening several of the collectors remained near their paintings for some time, even taking pictures with them, etc. in some cases.

Regarding the reasons why some collectors prefer to remain anonymous, we understand for example that some don’t want to be badgered to sell their works, some collect for truly personal reasons and it doesn’t make sense for them to share with people outside their circle of relationships, and some would prefer not to be given the collector label, and there are certainly other reasons that we don’t know of or which we don’t recall at the moment.

Installation view; Sara & André, O Colecionador de Belas Artes [The Fine Art Collector]; Galeria Quadrum; 2022. © Bruno Lopes

DP: As for how this work of yours might itself be collected (and without being entirely serious), perhaps it would be a curious outcome if the series was split up and the paintings were dispersed among different collectors. Metaphorically, this would lead to a kind of virtual infiltration of the collections into one another, or even the imaginary materialisation of unfulfilled wishes for acquisition, who knows? On the other hand, perhaps some collectors would only want to acquire the painting that concerns them directly? Several dynamics seem possible. The eventual breaking up of the series may even happen more fortuitously over time (as in the case of the Areal series, for example, of which the paintings have become scattered).

Will you fight to keep the series whole or allow it to disintegrate? In either case, what would be the important aspects in your opinion?

S&A: It’s a curious question and one that quite a few people asked during the exhibition. I don’t think that had ever happened to us before. All the works in our first solo gallery exhibition, Sara & André, held at 3+1 gallery in Lisbon in 2008, were made by other artists represented by that gallery using our persona and artistic practice as theme or subject, and we proposed precisely to all those involved, and in particular to the gallery owner Jorge Viegas, to only sell the exhibition in its entirety. However no one took our proposal seriously and we understand that it would be very complicated to sell an entire exhibition to a single buyer in the Portuguese market, especially from early-career artists. It’s not that that has never happened, but we know that it’s rare, a kind of jackpot that may happen once in a lifetime if you’re lucky. In parenthesis, we’ve heard of only three cases of this in Portugal since we started out in 2004. These episodes were relayed to us with an almost mythological air, referring to three exhibitions in museums or other prestigious institutions (not galleries) by three different artists. Curiously, the three exhibitions in question were sold to three different collectors, all of whom (we add now with some vanity) are present in this exhibition. Returning now to our work, except for some complete series that we have presented in group exhibitions and that are reserved to be sold together (we remember one from 2010 composed of four works and another more recent one composed of thirteen), it was never an option for us to think of a solo exhibition as a total commercial product because we don’t think it’s realistic. Besides that first exhibition in 2008, there are several other cases when we felt it would make perfect sense, such as the exhibition Exercício de Estilo, “dedicated to” Julião Sarmento at MNAC [National Museum of Contemporary Art in Chiado, Lisbon] in 2014, in which we did a fake retrospective with about thirty works in engraving, silkscreen, painting, sculpture, photography, video, etc., covering four or five decades of Sarmento’s career.

We thought it would be funny in this exhibition if each collector was barred from buying their own painting, but we gave up on that idea because we thought it might be a bit mean if the collector really liked “their” own work. It’s funny that one of the few (to date) who has purchased the painting from their own collection revealed to us that his favourite painting in the exhibition was one dedicated to another collector, but that he was unable to buy it instead of his “own”.

We wouldn’t say that we don’t care where the works end up, because that wouldn’t be true, but as a general rule we try not to be rigid or “controlling” with anything. Our only concern is that the pieces end up with someone who appreciates them (which could be us, ourselves, of course!) and with someone who will lend them to us if we ever want to show them again some day. It’s important to say before we finish that it’s possible that this series will grow a little, since until the book is concluded we will still try to involve some collectors we think are relevant and who we couldn’t include before. There is a 28th painting already under way and we think there’ll be some more over the coming months.

We end with a small personal anecdote. When the process of this exhibition was already under way, last summer, during one of our regular visits to exhibitions, we stopped by Galeria Nuno Centeno in Porto and saw some superb paintings by Ângelo de Sousa, whose provenance was the Ângelo de Sousa Estate. We really loved the paintings and asked the price out of mere curiosity, and Nuno told us that Ângelo always reserved what he considered the best painting of each series for himself or his family. A few months later, when this series was mostly painted and still in our living room, the main viewer of the works over about a year had been our son, so we asked him which painting he would like to keep for himself. He promptly replied: no need, I already have plenty of things in my room. During the exhibition, however, he changed his mind and told us he would like to keep the one with the tennis ball – Collector #4 – or, if that was not possible, the one with the basketball – Collector #12.

Sara & André; O Colecionador #4 [The Collector #14] and O Colecionador #12 [The Collector #12]; 2022. © Bruno Lopes