In the words of the great musician Nina Simone, an artist’s duty is to reflect their times. Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda, whose practice looks at where we are coming from and where we are going to with extreme precision, a warm understanding, and an impeccable humour, confidently performs this definition. Having employed mainly photography at the beginning of his career, the conceptual concerns of his work and the post-medium condition in the arts led him to expand his practice over the last decade, and it now includes video, performance, sculpture, and large-scale installations. To delve into the artistic practice of Kiluanji is to plunge into a world of fantastic storytelling, where complex historic conjunctures meet accidental circumstances and personal anecdotes. He says coincidences don’t exist.

Kiluanji, who remembers countless lyrics by heart and knows appropriate songs for most occasions, started out as a guitar player, and jokes that all visual artists are frustrated musicians. Through his involvement as musician, producer, and lighting designer with the iconic theatre troupe Elinga Teatro in Luanda, he was introduced to the Angolan capital’s visual arts scene during the early 2000s. Having grown up in a house where politics was part of family life, with his father being involved in the struggle for independence and later serving as Minister of Economic Affairs during the Marxist-Leninist government of the 1980s, Kiluanji honed a critical thought that imbues his art with political consciousness.

Two prominent figures whom Kiluanji credits as major influences in his work sadly passed away this year. First, the South African photojournalist John Liebenberg: his legendary image archive comprises documentation of the apartheid regime in South Africa, the Namibian War of Independence, the South African occupation of Angola, and the civil war in Angola during the 1990s. Kiluanji learned a lot about Angola through the photographer’s images of the war, while living with John for two years in Johannesburg during the late 1990s. Studying his work, Kiluanji was able to grasp the implications of image production and understand how art could be used as a tool to denounce hidden and unfair realities. And second, the Angolan artist Paulo Kapela: born in the Republic of the Congo and based in Luanda since 1989, Kapela was a force of true freedom and wisdom in his generous way of being, living, and making art. Kiluanji dedicated the photographic series Garden of Images (2001) to Kapela’s mythical studio in central Luanda, which was a meeting place and a source of inspiration for many.

“Discovering Kapela’s work was a real epiphany. I was impressed by his capacity to mix media and juxtapose various levels of reality. He would collect a series of images of the city – magazines, bills, posters and newspapers – and use them to build altars. […] This mixture of religious, political and pop ritual, the living element and the huge freedom in the way he showed his work, unleashed in me the desire to approach lots of themes without specializing in anything, without fitting into any type of system. And there is no theme that I have looked at that isn’t already present in the work of Kapela.”(1)

The discussions that Kiluanji’s work contributed to over the years revolve around topics of collective memory and historical reflection, the aftermath of war, the legacies of colonial oppression, the urban environment and the use of public space, as well as the ways that numerous cultural influences in Angola coexist, are adapted, integrated, and transformed. The artist identifies a gap in time, a void that resulted from what he calls “being run over by history.” By this he means that when there are unresolved issues from the past that keep accumulating, it is hard to fully ‘be’ in the present. Kiluanji considers art as a vehicle to address these issues and build bridges from the past to the future.

Every so often the powerful from other lands came to rob us of tomorrow(2)

The series Homem Novo (New Man) (2009-13) comprises photographs, performances, and a video that Kiluanji produced in Luanda. In the photographic series Balumuka (Ambush) (2010), the ambushed characters are petrified Portuguese heroes that once occupied public space in the city. Having been removed from their pedestals immediately following Angola’s independence from Portugal in 1975, they were gathering dust in the courtyard of the 400-year-old Fort of São Miguel. Due to construction works at Largo do Kinaxixi, the anti-colonial warrior Queen Njinga Mbandi, erected in 2002, has recently been temporarily relocated to Fort of São Miguel.3 During the 16th century, Queen Njinga Mbandi was a prisoner in the same fort for resisting the colonisation. Her sister lost her life there. The 12 photographs portray the moment when the oversized bronze Queen returns, as if to seek revenge. There she is, waving her axe at the first king of Portugal Afonso I, and the poet Luís Vaz de Camões. At her feet, torn into four pieces, lies Paulo Dias de Novais, her contemporary, who founded Luanda and built the Fort. Military weapons, including cannons and Russian vehicles from the Cold War period, surround everyone.

However, the question about where to place these colonial monuments that represent violence and oppression remains. Removing them was already a way of dismantling and deconstructing a colonial consciousness, and a signal that these monuments don’t represent Angola’s history any longer. For Kiluanji, it is clear that the best and fairest solution would be restitution, sending them back to Europe in exchange for looted African artefacts that are housed in European museums. “All statues must fall,” affirms philosopher and curator Paul B. Preciado in response to the current toppling of statues around the world and in the context of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement:

“All monumental statues that commemorate patriarchal-colonial modernity would have to be taken down—absolutely all of them: the political, military, and ecclesiastical figures that compose the majority as well as the human traffickers, the doctors and scientists who espoused race theory, the solemn rapists and eminent génocidaires, and, not least, the writers and artists who produced the language and representations of power […] When a statue falls, it opens a possible space of resignification in power’s dense and saturated landscape […] That’s why all statues must fall.”(4)

Kiluanji’s work Redefining the Power – 75 (2011-12) emerged as a response to the pedestals, which previously hosted the colonial statues. Many of them remained empty throughout the civil war period, reflecting a void in terms of public debate and historic confrontation. Interviewed about the work, the artist stated: “It was exactly ten years after the war had ended in Angola. The city was starting to witness a cultural re-birth that I sought to express in the form of living monuments. The idea was to invite some crazy friends who live in a kind of constant performance to climb on the pedestals that were empty for more than thirty years, and have the freedom to perform whatever they want.”(5) Living heroes of local culture such as the poet and fashion designer Shunnuz Fiel, the performer Miguel Prince, and queer activist and fashion designer Didi Fernandes replaced the colonial stone heroes. According to Kiluanji, it should always be possible to alter monuments in order to reflect the era we live in: “I think every city should have empty pedestals that could be customized regarding our passions, instead of having representations in cold stone of dead people that no one really cares about today and most of them are connected with wars or political power.”(6)

Climbing on the plinths was a performance in itself, partially documented in the video Resetting Birds Memories (Reposição da Memória dos Pássaros) (2013), which added a layer of intricacy by including images of North Korean workers maintaining old monuments at the Fort of São Miguel. The photographs of Redefining the Power – 75 were taken as “afters” to postcards with the original monuments as “befores.” This proposal resonates with Preciado’s conclusion in the above-cited essay: “Let the museums remain empty and the pedestals bare. Let nothing be installed upon them. It is necessary to leave room for utopia regardless of whether it ever arrives. It is necessary to make room for living bodies. Less metal and more voice, less stone and more flesh. […] We do not need any more statues. Let’s not ask for marble or metal to fill those pedestals. Let’s climb up on them and tell our own stories of survival and liberation.”(7) It is significant to note that Kiluanji’s reflections precede the BLM movement’s toppling of statues by ten years. In various former colonies, including Angola, the dismantling of monuments and the critical acknowledgement of their symbolic power took precedence, as it played an essential role in the rebuilding of national identities.

The series title New Man ironically cites the Angola’s anthem. The sentiment that accompanied the birth of the nation in 1975 echoes Martinican psychiatrist and anti-colonisation political leader Frantz Fanon’s last sentence in The Wretched of the Earth: “For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must turn over a new leaf, we must work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man.”(8) It was a long struggle for independence, lasting 14 years. Portugal, which in 1951 declared that all its colonies were to be called “overseas provinces” in an attempt to minimise international criticism, did not want to leave. Instead Portugal was claiming that Angolans felt Portuguese. The extreme violence of the Portuguese Colonial War (1961-1974) should have been enough to debunk the “good coloniser” myth that still prevails in Portugal, where the “Portuguese Discoveries” are taught in schools with an unconcealed sentiment of pride. Little to nothing is discussed about the centuries of perpetual looting and racist oppression of peoples. Fanon condemns Europe’s supremacy: “Leave this Europe where they are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of every one of their own streets, in all the corners of the globe.”(9)

Acting against this lack of reflection in Portugal is Djass – Association of Afrodescendants (Djass – Associação de Afrodescendentes, Lisboa), which submitted the project Memorial to Enslaved People to Lisbon’s City Council in 2017 through the Participatory Budget initiative. The Memorial is a long-overdue tribute to the millions of African people who were victims of the transatlantic slave trade or were enslaved by Portugal between the 15th and 19th centuries. The project was awarded by popular vote and will be installed at Largo José Saramago, a public square in Lisbon’s historic centre near to the 35000-square-meter Praça do Comércio (Commerce Square), which used to be the main entrance to the city from the Tagus River. Kiluanji’s Plantation (2021), the selected proposal, comprises four hundred 3-meter-high sugar cane trunks produced from black aluminium, thus mimicking a monoculture plantation of the raw material that is intrinsically connected to the history of slavery. A gathering space in the form of a small amphitheatre is placed at its centre. This powerful and immersive setting creates a mental and physical environment devoted to the transcontinental trauma of enslavement and exploitation of human life in order to consider its legacies in the present and project possibilities for abundant futures. There are no words to express the magnitude and relevance of this new memorial in the capital city of Portugal, where numerous statues celebrating the “Age of Discoveries” have yet to be toppled.

Carrying the marks of the whole history of indigenous humiliation on her body(10)

Following the independence attained by Angola in 1975, a devastating civil war took over the country for 27 years. This war only ended in 2002. Kiluanji was 23 years old. Initially a conflict between two of the liberation movements, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), the dispute quickly escalated into a proxy of the Cold War with interventions from the Soviet Union, Cuba, South Africa, and the United States. For the artist, this was defining: “I have always had the feeling that I have experienced the direct consequences of the globalisation of war. Since I was a child I have learnt that in Angola we were part of, or victims of, a great international strategy, and that what was happening was not caused only by our will. You are therefore compelled to adopt a position. I think that this awoke in me a concern for tackling themes on a broader scale.”(11)

Angola’s first president, the Marxist doctor and poet António Agostinho Neto, gave his inaugural speech in 1975 next to a bust of Lenin, using a phrase that Kiluanji later appropriated as title for his multi-media installation Under the Silent Eye of Lenin (2017). There is a paradox between the cited phrase containing a display of idolatry, as if Lenin was watching from somewhere, and the categorical rejection of religion by communism. A similar combination happened during the Cold War, during which science fiction became enormously important to create images of invincibility, both in the Soviet Union and the United States. In Angola, soldiers would tell surreal stories about tele-transportation, bullets that couldn’t kill, and other fictions of supernatural powers. These stories were necessary companions to face fear and sustain the war. For the installation, the artist created three busts of Lenin in the form of Nkisi, i.e. sculptures inhabited by spirits that are used in witchcraft rituals. Artisans of fake Nkisi produced the wooden statues, which were then installed in a kind of shrine to Communism, amplifying the contradiction threefold. A video documents the fabrication of the fake Nkisi and features a Russian voiceover of Lenin that speaks about his experience in the first person. Kiluanji’s humorous provocation points at the way Marxism was uncritically followed as a dogma in analogous ways to religious believes, but it also unpacks the intricate psychological dimensions of the conditions imposed by war.

Likewise inspired by the words of Agostinho Neto is Kiluanji’s work Havemos de Voltar (We Shall Return) (2017), which is part of the series In the Days of a Dark Safari (2017). Havemos de Voltar (We Shall Return) is a short film titled after the eponymous poem by Agostinho Neto that calls for a return to pre-colonial Angola, its liberated land and its traditional customs. Unfortunately, such total return would require two evident impossibilities: the erasure of long periods of violence, and the fantasised existence of this pure place. The longing for an idealised past is illustrated through the story of Amélia Capomba, and narrated from her own perspective. Amélia is a stuffed giant sable antelope—a critically endangered animal and symbol of Angola—living in an archive centre. Due to an oversight of the taxidermist, her brain wasn’t removed and she can still remember the forest, her home. Amélia speaks of her yearning to return and vehemently rejects her present condition as objectified historical piece of decoration. Gradually, we understand that her supposed ancestral memories are nothing but the stylised dioramas of the Natural History Museum—a complete fiction. Her wish to escape comes true when a Chinese businessman, unable to convince the Museum director to sell him the antelope as decoration for his nightclub, sends a group to steal her. Amélia is happy outside, thinking she is finally returning to the desired forest. She finds herself in the club, where she steps into a time portal opened up by the music. Regrettably, she doesn’t emerge in pre-colonial Angola, but in the midst of the South African invasion of the country.

In the world we want, everyone fits. We want a world in which many worlds fit(12)

The civil war in Angola sparked a severe humanitarian crisis that involved millions of internally displaced people, many of which sought refuge in the capital city of Luanda. In Kiluanji’s words: “The war was far more localized than it seems, far more real, and it didn’t take place only in offices and factories but in homes, on street corners and in the forest. To the extent that I don’t want to explore this history from an all-encompassing perspective, but rather to examine this more detailed part of the war, how it occupied our time, our thoughts and our dreams. It is an atmosphere, a vibration. It is the air we breathe.”(13)

Displacement and migration have been recurrent topics in the artist’s work, but two recent short films directly address the memories of the war most strikingly. Phantom Pain – A Letter to Henry A. Kissinger (2020), shot entirely on the street where the artist was born and raised, is an accusatory letter to the former US Secretary of State (1973-77), a reminder of his direct responsibility for death and misery in Angola. According to C.I.A. officer John Stockwell, cited in the film, Kissinger ordered the C.I.A., which was deeply implicated in supporting South African’s invasion of Angola, to “keep the conflict alight.” Kiluanji reconstructs the real-life consequences of such brutal and revolting external verdicts through his childhood memories, including images of the largest Orthopaedic Centre in Luanda at the time, where myriad prosthetic limbs attest to recent agonies. Until today, abundant anti-personnel landmines and other unexploded bombs are still causing injury and death. Another work, There is no Light Inside the Mirror (2020) traces the psychological distress and trauma of those who experienced and fled the war. The modernist building in which it was filmed had been illegally occupied after independence, mostly by war refugees, and was dangerously overpopulated and degraded. Inside, there used to be all kinds of businesses, from brothels and churches to bars and markets. In 2018, the inhabitants were relocated, leaving an empty building behind. The film narrates the story of Emanuel Tchisseke in the first person. Tchisseke escaped from eastern Angola and occupied an apartment on the 14th floor. His shadow becomes the metaphor for his dark visions and nightmares, as he lives his days and nights in loneliness, pain, and deep anguish. In a desperate attempt to destroy this sorrow, Tchisseke throws his shadow down from the top of the building.

The two video works, Phantom Pain – A Letter to Henry A. Kissinger and There is no Light Inside the Mirror (both 2020), thoughtfully look at the wounds that are still open in Angolan society. At the same time, they humanise the victims, so often reduced to mere numbers, bringing their plights to the fore and thus allowing for renewed empathy. The same dehumanisation is taking place today. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that there are over 79 million forcibly displaced people around the world, including asylum seekers, refugees, and stateless people. These individuals and families, who are fleeing war, ethnic persecution, extreme poverty, and climate disasters, not only have to endure undignified conditions over extended periods of time, even decades, but also have their very lives criminally deemed disposable.

The issues around forced migration need to be framed within a wider global context of pervasive racism, which is what ultimately allows for the on-going atrocities to happen. “Racism is the state-sanctioned and/or extra-legal production and exploitation of group differentiated vulnerabilities to premature (social, civil and/or corporeal) death.”(14) The causes for forced migration, the need to undergo dangerous passages to flee, and the hopeless realities on the other side in case the intended destiny is even reached, all sprout from the same rotten root. The suffering of racialised bodies of people from Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Somalia, Central America, Colombia, Venezuela, Myanmar, Burundi, and many other countries, is appallingly normalised. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange once mentioned in an interview that we all just care about our backyards, but that the size of it differs from person to person—someone’s might be a tiny 2 square meter box, someone else’s might encompass the whole world.(15) The perceived distance to tragedies that are not in our immediate vicinity, which allows for people like Kissinger to command fatal blows remotely, is actually a delusional construct. A catastrophe is certainly no less severe just because it’s taking place thousands of kilometres away from my home, or because the victims are not my friends and family. We need to recognise this fallacy and urgently expand our backyards.

The mixed-media installation The Isle of Venus (2018) is a continuation of Kiluanji’s research that started in Venice during 2010 and that examines the topic of migration from Africa to Europe (Self-Portrait as a White Man, 2010). The dominant xenophobia is absurdly contradictory to the fact that many of the palaces in Venice and other cities were built by enslaved African men, referred to as Black Moors. This history is largely omitted in most European art and literature, perpetuating misconceptions about migration. Reflecting on one of the largest humanitarian tragedies of today, namely the shameful shipwrecks in the Mediterranean that happen under the close watch of Fortress Europe, Kiluanji’s layered installation translates capsized boats into an archipelago of illusory islands. These are islands in between two continents: one continent can’t embrace its children, and the other continent is scared to death of adopting them. “Untouchable” symbols of Western heritage in the form of miniature Greco-Roman sculpture, such as the Venus de Milo and David, are placed on concrete plinths and covered with brightly coloured condoms. They are eternally memorialised, safely protected from external agents, and utterly sterile, with no possibility of procreation. An archive of images featuring migrant boats crossing the Mediterranean is placed on the wall. The boats are obstructed from view via black squares, and the room is filled with a song of sorrow by Ngola Ritmos that tells the story of a disappeared child.

One of the main non-economic reasons for European countries to reject refugees is the desire to “protect” their own culture and ways of life. To think of a large number of foreigners “invading” and bringing with them their own cultures and traditions and belief systems is perceived as a threat to their nation’s identity by the local populations, particularly in countries where this fear is further instilled by nationalist governments, as for instance in Hungary, Austria, or Switzerland. How can these emotions of cultural territoriality be deconstructed and the related anxiety accurately examined? The separation created by the fear of the “other” must be radically transformed into possibilities of identification that lead not only to solidarity, but also to healthy hybridisation processes.

These preoccupations are similarly at the core of Something Happened on the Way to Heaven (2019-20), an exhibition that includes several works developed during a residency on the Italian island of Sardinia. The idea of an idyllic paradise is reversed, and what emerges is a militarised hell with traces from the Cold War, US military bases, and a history of harmful military testing. Sardinia is also an island where many undocumented migrant boats are headed. Again, idealised images of freedom, peace, and a new life in Europe are countered with stark realities beyond anyone’s worst nightmares. Reliquary of a Shipwrecked Dream (2019) is a “homage to migration understood as an existential condition of diaspora and as an inescapable part of human life, whether forced or chosen.”(16)A bronze head rests on a column of salt from the Mediterranean Sea, caged within a metal fence structure. The features are those of Angolan actor Orlando Sérgio, Kiluanji’s long-time collaborator, who was the first Black immigrant to interpret Shakespeare’s Othello in a Portuguese production at the Municipal Theatre of Almada in 1993.

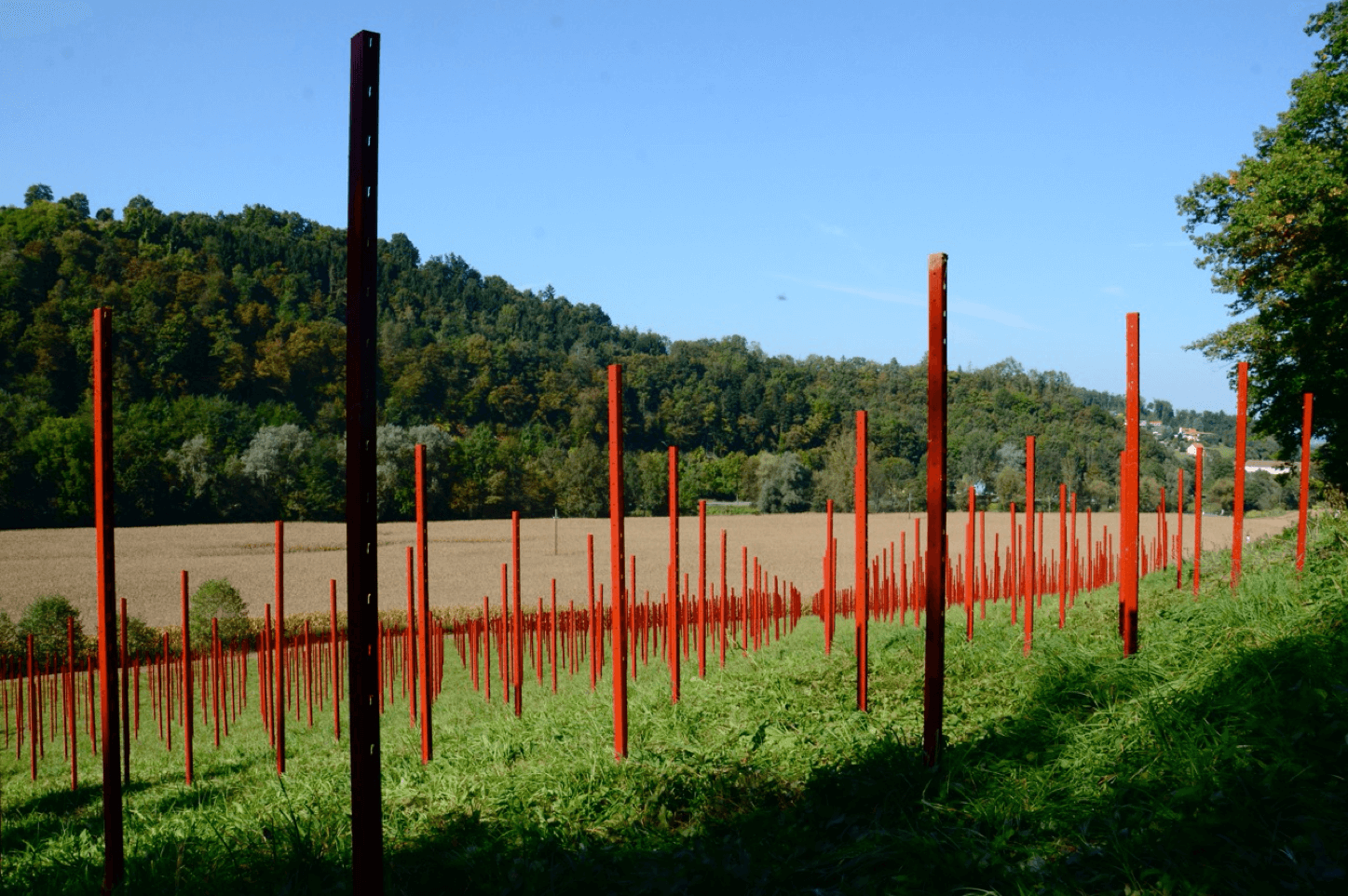

Another work dedicated to the lost lives in and around Europe is This Is My Blood (2016), a large-scale installation in the region of Leibnitz in Austria, close to the border with Slovenia. Creating a parallel between the wooden structures of the serene ubiquitous grapevines and the violent metal fences that were recently erected at the Austrian borders, this work consists of 2000 steel rods—the same rods used for the fence. Now painted in dark red by the artist, the rods puncture a landscape that imitates, and could eventually become, a grapevine. A reference to the region’s pervasive Catholic tradition is embedded in the title of the work. Kiluanji thus evokes Jesus’ words relating to the wine he shared with his disciples in the Last Supper. The work is a reminder of his teachings and prayers for compassion, as well as a call of how the opposite is being practised today. The blood red paint on the 2-meter-high bars is not a signifier for the blood sacrificed by Jesus to forgive all our sins, but a symbol for the tragic deaths of refugees trying to reach Europe that, on the contrary, incriminates us.

Kiluanji’s work does create ingenious bridges between ‘whens’ and ‘wheres’. His incessant curiosity about Angola’s past and collective psychological processes of nation building results in relentless interrogations of complex geopolitical constellations. With hybrid Luanda and contemporary ruins as main inspirations, the artist traces the connections of his hometown to Europe, Brazil, Cuba, the Soviet Union, the United States, and beyond, “making distances shorter and improving dialogue.”(17) Most significantly though, the works themselves are located in a liminal space from where it is possible to see both sides of the same coin. There is no paradise without hell. One inevitably implicates the other. “The money of those who do not give is the labour of those who do not have.”(18) With the infinite contradictions in mind that he eloquently articulates in his works, Kiluanji has been asking himself lately “Is God a Communist?”, a suitable title for this brief survey of his moving and thought-provoking art. Now, Kiluanji, what song shall we play?

References

Afonso, Lígia. “Entrevista a Kiluanji Kia Henda” in BES Photo 2011. Lisbon: Banco Espírito Santo / Museu Colecção Berardo, 2011.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Books, 2014.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Wivenhoe, New York, Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Hossfeld, Johannes, ed. Kiluanji Kia Henda. Travelling to the Sun through the Night / Viajando ao Sol durante a Noite. Göttingen: Steidl; München: Goethe-Institut, 2016.

Knoppers, Kim. Interview with Kiluanji Kia Henda. 20 May 2015

https://www.foam.org/talent/spotlight/interview-with-kiluanji-kia-henda

Marcos, Subcomandante Insurgente. Our Word is Our Weapon: Selected Writings. New York, London, Sydney, Toronto: Seven Stories Press, 2001.

Moraes, Vinícius de. Berimbau. 1963.

Poitras, Laura. Risk. 2016.

Preciado, Paul B. “When Statues Fall” in Artforum December 2020.

https://www.artforum.com/print/202009/paul-b-preciado-84375

Ribeiro, Anabela Mota. “Kiluanji Kia Henda” in Público. 20 March 2011.

https://www.publico.pt/2011/03/20/jornal/kiluanji-kia-henda-se-acontecesse-alguma-coisa-em-angola-seria-mais-parecido-com-o-que-se-passa-na-libia-21553409

[2] Marcos, 2001, p. 245.

[3] Kiluanji’s forthcoming performance piece Red Light Square tells the story of the metamorphosis of the public square Largo do Kinaxixi from pre-colonial times until today.

[4] Preciado, 2020.

[5] Knoppers, 2015.

[6] Idem.

[7] Preciado, 2020.

[8] Fanon, 2014, p. 255.

[9] Fanon, 2014, p. 251.

[10] Marcos, 2001, p. 5.

[11] Afonso, 2011.

[12] Marcos, 2001, p. 80.

[13] Kiluanji Kia Henda in Hossfeld, 2016, p. 146.

[14] Ruth Wilson Gilmore cited in Harney, 2013, p. 42.

[15] Poitras, 2016.

[16] Exhibition label at Galerias Municipais – Galeria Avenida da Índia, 2020.

[17] Ribeiro, 2011.

[18] Moraes, 1963.