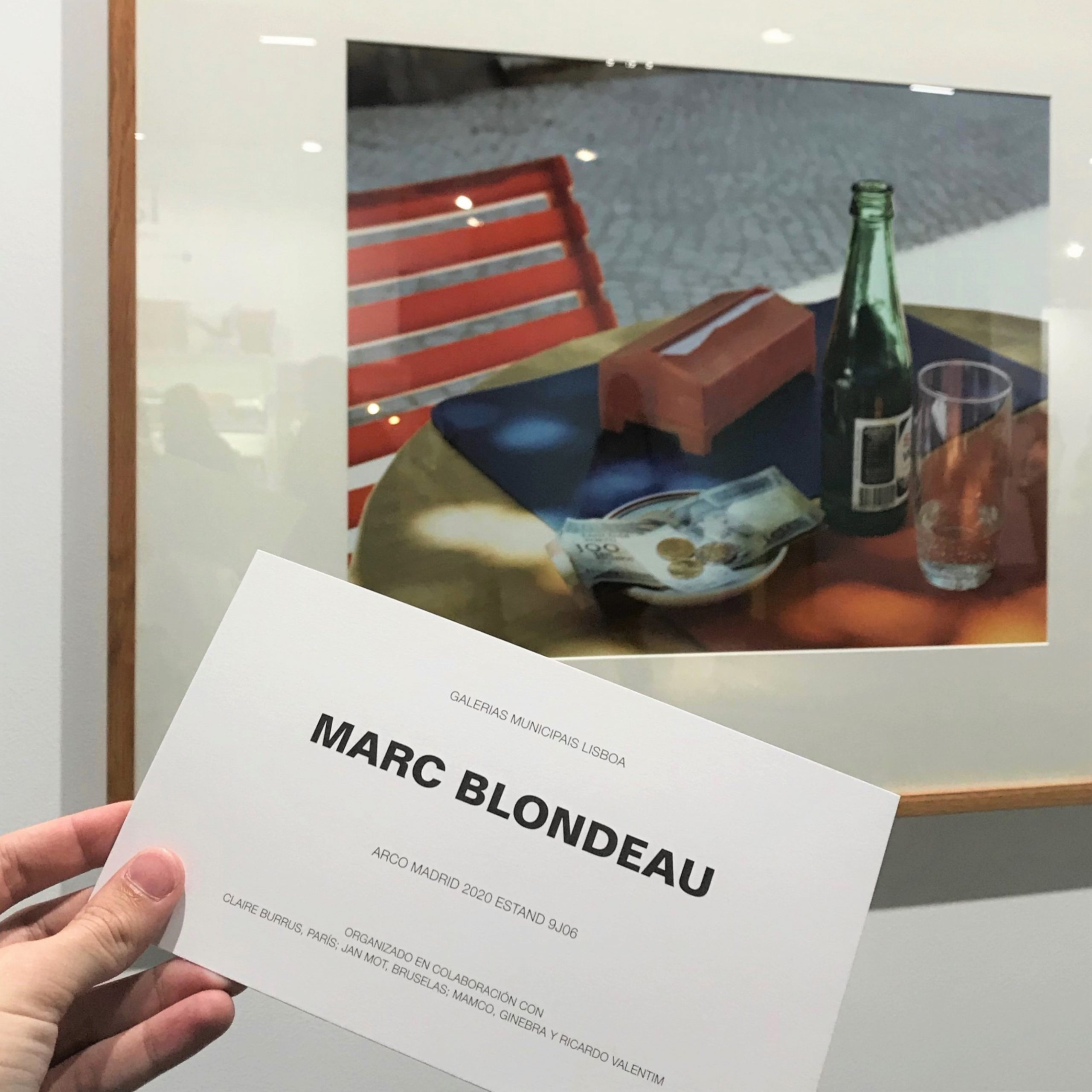

In late February 2020, Galerias Municipais de Lisboa took part in the ARCOmadrid contemporary art fair for the third time. At its stand the Galerias Municipais presented the work Lisbonne (1991) by Marc Blondeau. The colour photograph, one of a series of eight photographs by Blondeau, depicts a common, everyday scene in the city whose name it invokes. A street café table in the sun with a number of objects on it, including a half-empty water bottle, an empty glass, a serviette dispenser and a saucer with money and a receipt in it – elements that would indicate that the table was occupied shortly before the photograph was taken. What at first sight would appear to be a generic image of a street café, reveals via specific details that it is a very personal photograph of the city of Lisbon; the footpath in Portuguese paving; the 100 escudos note featuring an image of Fernando Pessoa; and the receipt on which one can read the name “Confeitaria Valbom”, a café just over 100 metres from the Gulbenkian Gardens, and still operating in the same place today. The photograph was taken on Avenida Conde de Valbom. All of these details may go unnoticed when one first looks at the image, but they are elements that help to understand more concretely that the dimensions of time and space are very well defined in the image. “It is an archetypal representation of the city that evokes a sense of nostalgia for a now bygone era (…).”[1] It is a straightforward document, akin to publicity, of a walk through the Portuguese capital. It is a registration of that event and a registration as an event.

Devoid of anything that could serve as an attention-getter, the art fair booth’s white wall featured only this one photograph. The name on the adjacent label identified the work and its creator. Perhaps precisely because the visitor was confronted with a stand that was so “exposed”, it was understandable that the photograph generated a certain amount of perplexity in the fairgoers who walked by the stand. Together with the photograph on the wall, a table at the stand featured a stack of invitation cards alluding to the project and three sheets of information explaining in Portuguese, English and Spanish what the work was about and also containing information on Marc Blondeau, a collector and art dealer. The press releases also provided background information on the work of Philippe Thomas, a visual artist and the original creator of the work presented at the stand.

The name Philippe Thomas is by no means one that is part of the mainstream in the international art discourse. The art critic and historian Elisabeth Lebovici has written that his obscurity can be attributed essentially to two reasons: Thomas’s own conceptual practice and an art criticism that relies on discourse mechanisms rooted in European and North American art.[2] From the late 1970s onwards, his work began to address practices such as institutional critique, in an endeavour to conceptually depict his professional art network as a means for his counter-hegemonic creative practice. These issues became clearer when, in the 1980s, Thomas began to gradually eradicate his own name and identity (Daniel Bosser, Philippe Thomas décline son identité, 1987) from his work. Through his communication agency, readymades belong to everyone®, which was set up in 1987 on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition at the Cable Gallery in New York, Thomas offered collectors the possibility of subscribing to and becoming part of the history of art; they could “become great artists without the pain, anguish and poverty.” This was achievable through the acquisition of and simultaneous subscription to a work of art by him, the authorship of which was transferred to the name of a collector. In other words, Thomas was ceding authorship of his work to acquiring collectors, replacing his name with the names of the collectors of the works. Said collectors not only then owned a Philippe Thomas work when they acquired one, they also became the author of said work. Thus in Thomas’s art works, the name that features as the name of the creator of the work is rarely his own; his name has been replaced by many others that now feature on the labels and in the records and databases of museums and collections. In the midst of the great art market boom and the emergence in force of the neoliberal economic measures and policies and the restructuring of the museum and institutional universe, Thomas’s disappearance act challenged the historicisation processes and the models according to which history is written, by erasing his name from the discourse and the art world altogether. In his work, he identified how the artistic object, criticism of the institutional models and the artistic persona were conflated in an antagonistic way. Through the agency set up by himself and the process of deconstruction of his identity he revealed and called into question the artistic model and the system themselves, exposing the paradoxical plot between art, authorship, output, the market and capital.

Returning to the invitation card placed on the table at the Galerias Municipais stand in Madrid once more, which, as pointed out above, presented one single work, one can read in the final line: “Organised in collaboration with Claire Burrus, Paris; Jan Mot, Brussels; MAMCO, Geneva; and Ricardo Valentim.” One should, perhaps, explain who these people are, beginning with Claire Burrus, a former gallery owner and the executor of Philippe Thomas’s will and estate, a task to which she has dedicated herself since the closure of her gallery in 1998. Since 2013 Burrus has been representing Thomas together with Jan Mot, another gallery owner and the current representative of Thomas’s work and his agency, readymades belong to everyone®. The label for the photograph on view also made it clear that the reference to MAMCO Genève (Geneva Museum of Contemporary Art) on the invitation and the information sheets was related to the fact that MAMCO was indeed the museum and the collection where the work had been loaned from. Finally, the reference to Ricardo Valentim, the artist invited by the Galerias Municipais to carry out the design project for, and present a work at the stand of Galerias Municipais at ARCOmadrid 2020. Similar to Philippe Thomas, who disappeared from his own work behind the names of the collectors who acquired it, Valentim also seems to have “disappeared” from the project. What at first sight may appear to be a presentation of a single photograph depicting a Lisbon street café, reveals the plot and the whole machinery in which Valentim participates.

At the invitation of Galerias Municipais’ director Tobi Maier, Ricardo Valentim proposed presenting the work as a “representation” of Lisbon’s Municipal Galleries, and simultaneously a “representation” of the city of Lisbon in Madrid. Lisbonne (1991), by Philippe Thomas, was purchased by Marc Blondeau, and, as a result, it became a creation of the latter, applying the model implemented by the readymades belong to everyone® agency. Later, Blondeau deposited the work at MAMCO Geneva, where it is now part of the collection. With Lisbonne (1991) by Marc Blondeau, Valentim decided to present a work created by a collector, from which the original creator seems to be absent and alienated (but for the representation of Fernando Pessoa on the 100 escudo note reminding one of the poet’s many heteronyms, which, as is known, was an inspiration for Thomas’s work). Valentim’s decision to present a work that is part of a museum collection and display at an art fair is somewhat antagonistic to the context itself, given that one would expect a work presented at a fair to be for sale. What Valentim presents in this project is the registration of a plot and its entire machinery, framed by the exhibition period at the fair and the graphic materials, namely the invitation card (ephemera) and press release designed by Valentim himself.

A few weeks after the ARCOmadrid 2020 fair closed, the IFEMA (the Fair Institution of Madrid) space was converted into a mega-field hospital, a huge installation of approximately 5,000 beds distributed throughout the 35,000 sq. metres of multipurpose pavilions. The walls and dividers that defined the fair stands now gave way to an open, bare space that was to receive patients infected with the novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). These patients could not be treated in the Spanish capital’s hospitals, as they were full, indeed at breaking point. The image of this temporary hospital installed in the empty fair pavilions brought home the full impact of the pandemic – a pandemic, which, in line with its condition of subversion of “normality” shone a light on the sharply growing shortcomings in social services. That very virus, due to its pandemic dimension, reveals and exposes the social and economic inequalities that are built into the models of “normality”. Inequalities, which, in a global state of emergency such as the one we have been experiencing, will continue to discriminate, in alliance with and through the interlinked powers of nationalism, racism, xenophobia and capitalism.[3]

In his book, Le Theatre et son Double (1938), Antonin Artaud pinpoints some of the relations between theatre and the plague which, when read in the context of the current pandemic situation, are particularly resonant: “The plague takes images that are dormant, a latent disorder, and suddenly extends them into the most extreme gestures; the theater also takes gestures and pushes them as far as they will go: like the plague it reforges the chain between what is and what is not, between the virtuality of the possible and what already exists in materialized nature.”[4]

Taking Artaud’s idea of “theatre” and expanding its semantic value to include the notion of “machinery”, it is possible to identify relationships with Ricardo Valentim’s project. Just as Thomas did through his agency, Valentim now does through this artistic project: the roles are inverted and the acts, described above (author, collector, work, institution, etc.), together form a play which, by staging this whole process and antagonistic plot, subverts the cultural notions and constructions associated with authorship, the artistic object and the institutional models, and also the notions associated with the market-related questions of reification. Valentim “stages” this play, which, by subverting the basic notions of display modes in the context of an art fair, precisely exposes and also questions the material, virtual and cultural hegemonic means that are at play in that matrix. The invitation card remains for posterity as a document of, and indeed as, the event.

[1] The press release for the project Marc Blondeau, https://galeriasmunicipais.pt/exposicoes/marc-blondeau/ (accessed on: 19.01.2021).

[2] Lebovici, Elisabeth (2018), The Name of Philippe Thomas, Kusthalle Bern: Bern, Sternberg Press: Berlin.

[3] Butler, Judith (2020), Capitalism Has its Limits, Verso Books, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/4603-capitalism-has-its-limits (accessed on: 19.01.2021).

[4] Artaud, Antonin (1938), The Theater and Its Double, Grove Weidenfeld: New York, Ed. 1958, p. 27.